A Brief Survey of Tasteful Evil

On seeing The Zone of Interest in a flooded movie theater and The Curse

Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest has been nominated for Best Picture, which means that far more people will see a claustrophobic, experimental film about Auschwitz than one could possibly imagine. For nearly all of these moviegoers, the experience will go something like this: a solemn arrival at the theater, the intentional omission of snacks, or at least popcorn, as a show of appreciation for the stakes, a bombast of wildly misplaced trailers for films like Argylle (a movie that appears to be mostly about a cat), a clipped credit sequence, and then a mechanical dirge behind what feels like an interminably startling black screen. The film begins with a shock presumably to denaturalize your experience, to orient you in the gruesome logic of the experience to come.

Me, well, my Zone of Interest experience went more like: drive through torrential rain, dodge fleeing moviegoers as they stumble through the knee-high water of the theater’s parking lot, brace myself after finding parking on high ground, wade through the same flooded lot, wrestle glass doors open to slosh into a similarly flooded theater lobby, huddle up with party (girlfriend, friend), decide that these were $12 we’d never get back from Fandango and, well, we were already inside, confirm with tremendously overwhelmed theater employee that the film was still rolling and that, no, they had no plan, pay for two Miller Lites despite being at this point ankle-deep in what I can only assume from the comfortable remove of time was raw sewage, and plod into my seat. And so this is how I met The Zone of Interest’s wall of noise: soaking wet, in a flooded movie theater, approximating some facsimile normalcy so as to make sense of the fact that I might be forced to sleep at the theater whose bathrooms had been rendered unusable by what was by then waist-high flooding. What I mean is that I more or less saw The Zone of Interest in 4D.

I don’t want to write too much about The Zone of Interest, because it has become the sort of film that creates unbearable moralists and snobs of both its converts and its detractors. It’s also difficult, in terms of human limitations, to engage too deeply with a film meant to make you feel uncomfortable when you are already, physically, as uncomfortable as you have ever been in a theater. But at the risk of sounding like a multi-paragraph Letterboxd reviewer, it feels important to insist that The Zone of Interest is not just a film about the banality of evil; there’s already a book for that, and for the vast majority of people who’d prefer not to read, that book has a remarkably portable title. But I want to offer a challenge to those of the film’s critics whose chief complaint is that Glazer did not depict enough of the horrors of the Holocaust: what if it’s held back by the fact that it showed too much? Glazer’s Auschwitz looms behind the Höss’s fence; its unconscionable sufferings haunt the film’s sound design. This is a film about the most vile cognitive dissonance imaginable, and it makes its point forcefully. But imagine a layer, two, three stripped back. Ask yourself: would it have been possible to create a film where, at any point, you as a viewer could convince yourself that the Hösses viewed themselves as human beings, much less good ones? How, knowing full well that any any given point in human history some act of staggering evil is likely occurring, do monsters convince themselves that they are the good guys? Is it by the clothes that they wear? The house that they tastefully appoint with stolen goods? The children, frolicking in the yard? When do they keel over and vomit, and how do they stand back up?

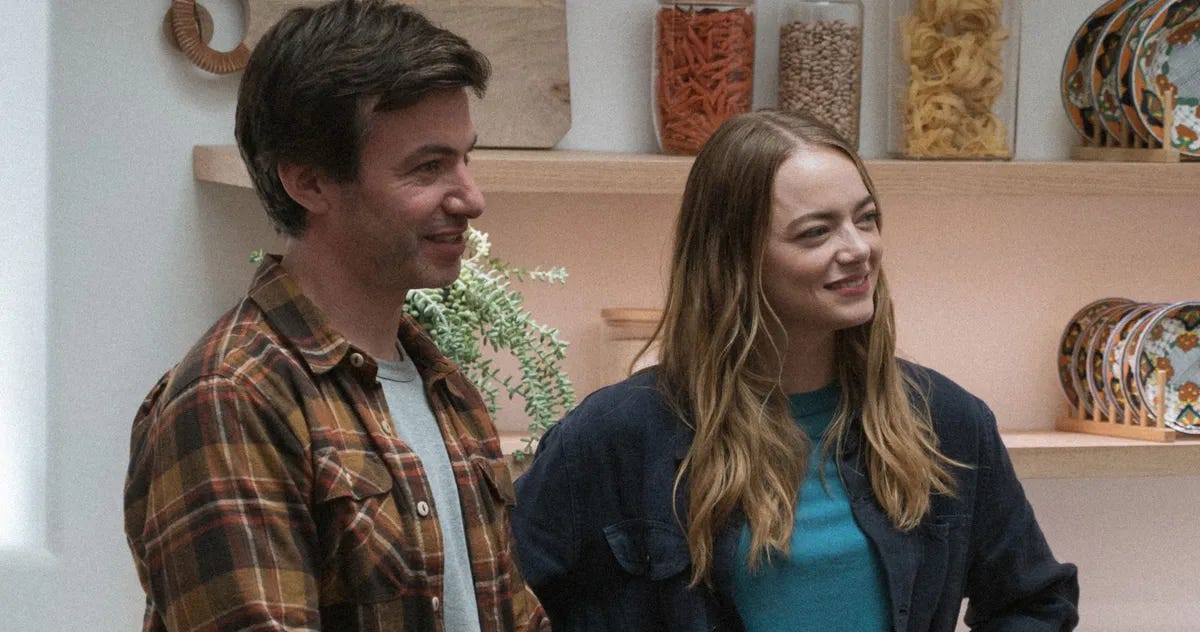

What I want to write about, really, is Emma Stone’s smile. That The Curse exists, as a major network television show in 2024, is a minor miracle. That the show overcame the sheer amount of buzzwords and signifiers used for its promotion—Safdie, Fielder, Stone, Showtime’s “Lynchian” new take on gentrification and white liberals, Jesus Christ—is a major one. The Curse is a major achievement, the type of show that merited more attention and discussion than it did, one that in a just universe would usher in an era of slow, challenging television that expresses its view of the world without inventing a traumatic backstory for each of its protagonists, but which in our universe will likely be forgotten outside of the expensive monthly bill I’ll pay to Paramount Plus after forgetting to cancel my subscription. And, well, it’s held together by Emma Stone’s contemptuous, self-deceiving, above-it-all smile.

The Curse is, above all else, a show about acting. Yes, the Safdie involvement means that many episodes are driven by a sort of manic, Oneohtrix Point Never-scored discomfort; and yes, its laughs are predominantly delivered via Nathan Fielder’s signature Lite Cringe. But both writers find themselves able to articulate something new by veering away from their respective commitments to verite or who’s-in-on-the-joke pranksterism and into the far more vulnerable realm of performance. And the show’s performer, beyond the shadow of a doubt, is Emma Stone. Stone plays Whitney Siegel, née Rhodes, the daughter of notorious Santa Fe slumlords who bankroll her passion project: environmentally-conscious, “ethical” gentrification. Whitney takes her husband, Asher’s last name, part of a concerted PR campaign to distance herself from the parents whose exploitative rent money she self-pityingly relies upon. The show follows the Siegels as they attempt to film an HGTV program, tentatively entitled “Fliplanthropy,” as a sort of promotional material for the hideous, eco-friendly “passive homes” that they’ve dotted the blighted Española community with; the hope, of course, is for the show to be big enough that white liberal gentrifiers move into these homes, turning the absurd speculative project into a sound investment.

It’s a meta-structure that, again, sounds intolerable when described, but it provides the backdrop against which The Curse’s showrunners and actors are able to meditate upon the role of performance as the necessary precondition for the effectuation of evil. Stone performs, obviously, in her role as Whitney, a character who outside the broadest strokes of white liberal feminism presumably bears no resemblance to Stone as human being (although, much of Stone’s recent fawning over fellow Best Actress-nominee Lily Gladstone has been imbued with a certain indefinable Whitney energy). But within the confines of The Curse, Whitney herself engages in her own performances: she performs a version of Whitney for “Fliplanthropy,” a version of Whitney for “Green Queen,” (the show’s later-season iteration) and, as it turns out, a version of herself in daily life. Whitney, it is revealed, brims with a thinly-veiled tendency toward the tyrannical, a disposition she feels it necessary to hide beneath that prefab Stone smile. The Curse works as an exploration of white liberalism on the strength of Stone’s performance alone, because it is she who transforms Whitney from the type of bumbling, apologetic caricature so safely skewered in popular media into a person who resents her obligatory ritual self-flagellation.

Stone’s Whitney seems at first obsessed with convincing people that she is a good person; as the show progresses, she reveals herself as someone who faults everybody around her for subjecting her to her degradation. What Whitney believes, in essence, is that she is entitled to displace brown people from their homes, using funds from her slumlord parents, turn a profit, and remain a good person. She debases herself in countless ways in service of this delusion. She remains married to Asher, a man she despises for his vacuous morality, cuck fantasies, and, well, tiny penis, a man whose weakness would comport well with her outward persona as an alpha female but for the fact that she doesn’t actually want to dominate her relationship. She brings a cameraman to a dinner at an art collector’s home, staging conversations to create the illusion that she is respected in the “art community.” She pays Cara, the indigenous artist upon whom she projects friendship and who evidently resents her, wages for a fake production job, for no evident purpose other than to keep her token friend of color in the mix. She puts her credit card on file at the garish jean store that she’s opened in town so as to ensure that any shoplifter is not arrested, racking up thousands of dollars a day in a stolen jeans tab run almost entirely by well-off white teenagers. She lets cameras into her home, then tries to use those cameras to confront Asher about their relationship’s failures where she lacks the interpersonal courage, all in the name of a terrible show that ends up on HGTV’s streaming platform.

Stone’s achievement is that she is able to portray each of these Whitneys—the HGTV Whitney, the apologetic liberal Whitney, and the resentful, petulant base Whitney—through subtle variations of that same smile-cum-grimace. Whitney takes pains to preserve appearances; no, literally, the act of keeping up appearances seems to cause her physical pain. In the moments where she breaks, whether dressing down Asher through cringe-core b-roll or barking at her slumlord parents that Española is hers, she evokes Sandra Hüller’s Hedwig Höss during The Zone of Interest’s most memorable exchange of dialogue: “I,” she hisses, “am the queen of Auschwitz!” If The Zone of Interest’s polite facade is routinely punctured by the sounds of unimaginable suffering that escape Auschwitz’s walls, The Curse’s tasteful liberalism is shattered by the resentment and entitlement bubbling just beneath its surface.

Both works take pains to make you, the viewer, terribly uncomfortable. But, as one establishes distance from their viewing experience, these depictions of a thinly-concealed barbarism can also have a falsely soothing palliative effect. I’m not evil, one tells themself, because I wouldn’t ignore the cries; I’m not evil because my liberalism is a natural and moral choice, not an obligation I resentfully fulfill. Both The Zone of Interest and The Curse are richer when the viewer rejects that comfort. When they ask how, in a moment of tremendous human suffering that either is abetted by or redounds to the benefit of the privileged class, one knows that they are actually one of the good guys. Are you telling yourself a story, or the truth?

Recently, I’ve been seeing a lot of prosecutors out. The experience never fails to ruin my day. I’ve seen prosecutors at Mardi Gras parades, smiling emptily at expressions of Black joy and Palestinian solidarity; I’ve seen prosecutors at concerts, bobbing their heads clumsily, asking me if we’re still on good terms. I feel in these moments not unlike the way it feels to see a racist on the Internet employ the exact vernacular and aesthetics I’ve come to consider tasteful. I wonder what they tell themselves in these moments, whether they craft stories to make sense of things or whether they don’t care. I wonder if a stranger, observing the crowd, would be able to identify a difference between me and them, and then I wonder if it matters.

This is very, very good. Thank you for writing so precisely about two of the most disturbing (complimentary) things I've watched in the past few months. The Curse is such an achievement, marked by Stone's maniacal yet effective acting choices and Sadfie's uncanny, genre-bending storytelling. It builds slow but envelopes you in an evil that's hard to penetrate but harder to shake. I love how you compared it to Zone of Interest, too. It's rather apt given the evil of that movie is also cloaked but occurring right in front of our faces, similar to how evil functions in our everyday lives. Both of them do an exceptional job of portraying a translucent evil, one that at times you feel is there but can't always see and your essay captures this acutely. Thank you so much for writing, please don't ever stop!