Civil War has nothing to say

On the nihilistic fantasy of Alex Garland's Civil War

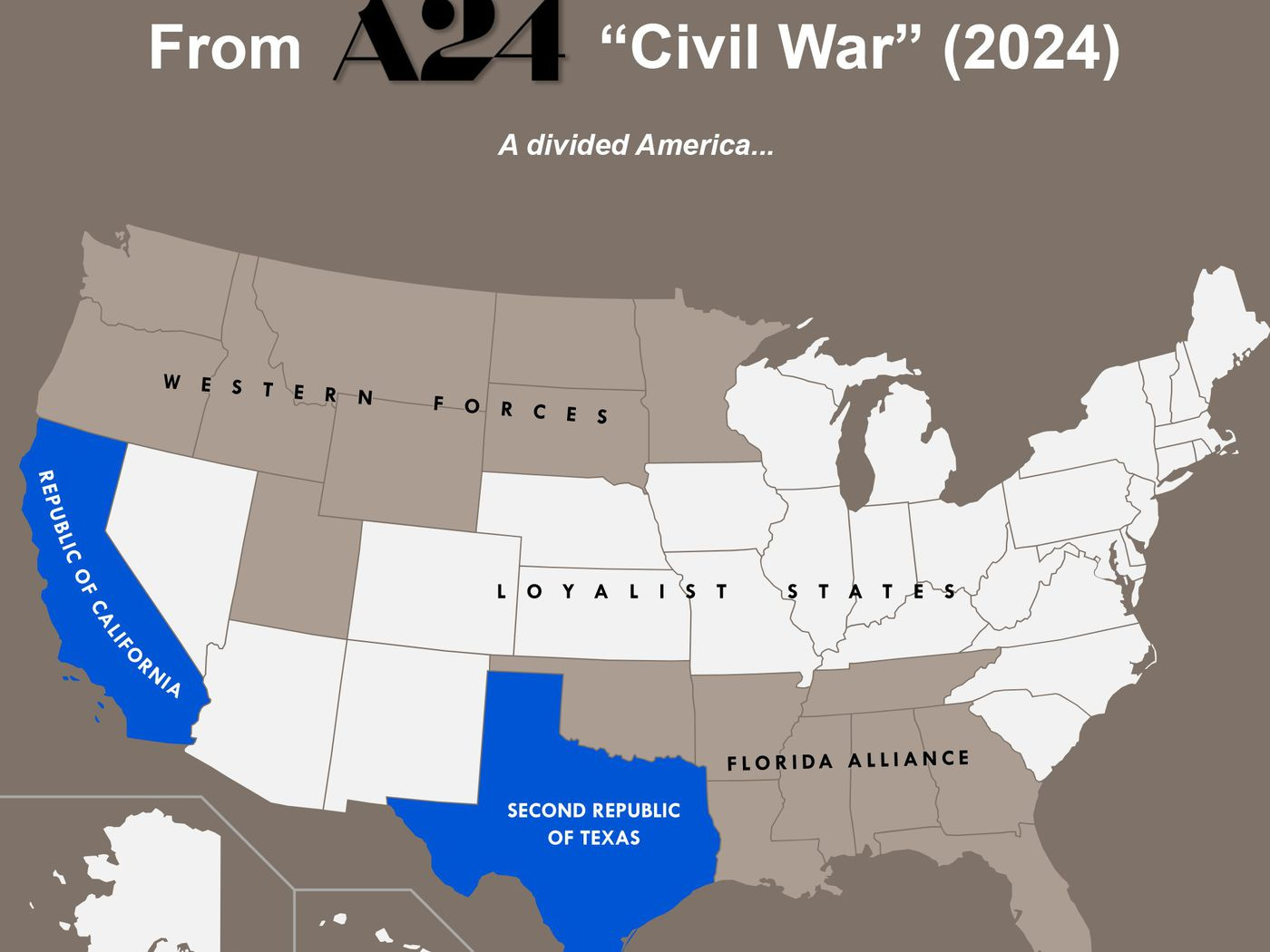

Any publicity, the saying goes, is good publicity. In an era of fleeting attention-spans and monetized online engagement, the premise is hard to dispute. And so I was unsurprised to learn that Civil War, the film I learned about when its asinine map of a divided America was roundly mocked on the internet, broke A24’s box-office-opening record (as funny and self-mythologizing a notion as Pitchfork’s recent boast that its review of Cindy Lee’s excellent Diamond Jubilee marked the publication’s “highest-scoring new album since Fiona Apple’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters.”) I can’t quite say how my hard-earned dollars became twelve of Civil War’s reported 44.9 million earned—hungover Saturday plans? a desire to participate in online discourse? Jesse Plemons? Whatever the case, I left the theater balancing a mild level of amusement and titillation against the painful feeling of having been catfished.

Civil War, the latest and supposedly final film from British writer-director Alex Garland, is a bait-and-switch. One walks into the theater expecting, on the basis of the movie’s advertising campaign and attendant conversation, a work of speculative fiction about a war-torn, vaguely futuristic America (a dreadful proposition in and of itself). One encounters, more dreadfully yet, a film about the power and importance of journalism. There’s no harm, of course, in a film subverting its expectations, but in order to subvert one must have something to say. On that front, Civil War has nothing.

Much of the criticism I’ve encountered about Civil War has been hung up, short-sightedly, on the movie’s lack of any overt political valence or explication. As friend of the blog Bilge Ebiri notes, a post-January 6th film that took pains both to imagine and choose sides in a contemporary American civil war would be, at best, unwatchable. So, too, does Max Read accurately commend Garland for resisting the urge to make what Read calls an “explainer movie,” the kind of lore-dense, Reddit-core endeavor endemic to a cultural imagination territorialized by spin-offs, sequels, and cinematic universes. Critics calling for Garland to take a side or comprehensively map out a history of his collapsed America seem to have reprehensibly craved a sort of liberal revenge fantasy, in which their worst fears about reactionary America were confirmed and their greatest bloodlusts slaked.

The fact that Civil War could have been a worse movie, though, does not make it a good one. The film follows a chosen family of four journalists at varying stages of their career as they embark upon a road trip through war-ravaged America from New York City to Washington, D.C. in the hope that they will be able to score an exclusive interview with the sitting, soon-to-be deposed president. The grizzled New York Times journalist (played by Stephen McKinley Henderson, who has become to safe grandfather-figure roles in the 2020s what Michael Cera was to beta males in the 2010s) muses that they shoot journalists on sight in D.C. The thrill-seeking, hard-drinking journalist (Wagner Moura) imagines asking the president if he regrets disbanding the FBI, drone-striking American citizens, or serving a third term. The calloused yet progressively war-weary journalist (Kirsten Dunst) lectures the aspiring journalist (Cailee Spaeny) about journalistic remove while her film-developing protege asks about, in one of the most embarrassing turns of dialogue I’ve ever heard, her big break photographing “the Antifa Massacre.” Where Garland engages in exposition, you wish he hadn’t, insofar as he exposes himself as a writer whose grasp of geopolitical possibilities begins and ends at “zombie apocalypse.”

The film settles into its episodic structure propelled more by Garland’s repeated Suicide needle-drops than any narrative stakes. The protagonists meander through Rust belt Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Charlottesville (for which any connection to the real-life Charlottesville as a site of racist reaction in America must be supplied by the viewer alone) on their way to the besieged capitol. On the way, they stare down sadistic rednecks at a gas station, embed themselves with (I can’t say the word embarrassing again, can I?) Boogaloo Boys executing American troops, riff with colored-hair paramilitary snipers, and are momentarily taken captive by a fatigue-wearing xenophobe (more on that later) attending to a mass grave.

At some point along the way, the why of it all—or, rather, the lack of any why—impresses itself upon the audience. The protagonists certainly have their answer: there is inherent importance, it seems, in being the last people to photograph the president before he dies. It’s only when they momentarily believe they won’t be able to accomplish this goal that any of them express feelings that one of their colleagues has died “for nothing.” But the question remains: why, for the overwhelming majority of people not insane enough to dodge gunfire for the privilege of documenting the carnage of war, does this matter so much? The film’s journalists tell themselves that their jobs are to get raw, objective information to the people; at one point, Dunst’s character goes so far as to suggest she hopes these people would interpret this raw information. In this sense, Garland’s film is a failure even taken on its own terms, for in its completely empty, nihilistic America, there exists no framework with which any imagined audience might interpret this supposedly invaluable journalistic grist.

I have seen people suggest that Civil War smartly subverts wartime journalism film tropes onto America by turning its shutters into the imperial seat; some go so far as to suggest the flatness and non-context with which Garland treats America is a wry play on the way that American audiences treat the countries that its government destroys. But there is a difference between choosing to say nothing and not having anything to say. As Garland’s repeated tidbits of explication make clear, he wants his dystopian America to exist in something like a cousin to the real world. Both in his visual language and hackneyed expository dialogue, Garland crams in more incoherent reference-points than Fall Out Boy’s maligned “We Didn’t Start The Fire” cover: the Boogaloo Boy’s Hawaiian shirts, references to “the Antifa Massacre” (a phrase, even in a fictional context, that should have one’s New York Times subscription automatically cancelled for a calendar year), obvious Trumpisms from the president (Nick Offerman), mentions of Portland Maoists, the phrase “The Florida Alliance.” Civil War doesn’t begin with a Star Wars-style scroll about the developments that led America into a second civil war not because of any directorial restraint, but because Garland’s understanding of American politics—and the American id writ large—appears shaped entirely by Bluesky users. He doesn’t abstain from finger-pointing to render his film more marketable—a notion that, hilariously, rests on the presupposition that American reactionaries would line up to see an A24 movie unless given a reason to feel offended—but because he doesn't, beyond the utterly useless notion of “polarization,” have any coherent theory as to how the United States could end up in crisis. Like any good newspaper, Civil War’s celebration of journalism is undermined by the dreck of the opinion pages.

The fact of Garland being in over his head in making anything like a statement about the nature of America pervades his film’s logic. Plot devices largely keep Civil War’s protagonists out of cities, where its director might have been forced to engage with a political vision more complex than a series of nihilistic boogeymen. Where the Italian filmmaker Luca Guadagnino rendered a startlingly evocative portrait of America in his allegorical road film Bones and All, the British Garland imagines America a particularly confounding set of Geoguessr locations; at one point, Dunst’s character instructs her mentee to photograph a burned-out helicopter in front of an abandoned J.C. Penney, gesturing lazily at a point about American sprawl and consumerism made more forcefully every other day on Twitter. Most inexcusably, Garland reveals a total inability to even begin interrogating the role that ideology, and its various sublimations, plays in the contemporary American hellscape.

The film’s signature scene—both its best and its worst—find Garland come closest to making a point. At the end of Civil War’s second act, its protagonists are held at gunpoint by two fatigue-wearing psychopaths. It’s not clear whether these men are loyalists, rebels, or autonomous chaos agents—one suspects that having to decide felt too complicated for Garland. As their captors slide dead bodies into a mass grave from their dump truck, the journalists are interrogated at gunpoint by the closest thing Civil War has to a villain (rendered brilliantly by a red-sunglassed Jesse Plemons). To establish the stakes, Plemons’ character executes an Asian journalist—introduced to the film five minutes prior. He grills the journalists: “what type of Americans are you?” The question is fraught with meaning. The horrified journalists stammer out their birth states. Missouri and Colorado, Plemons’ character confirms maniacally, are real American states. The jury is out on Florida, insofar as the Floridian character has a strong accent. Before we get an answer, Plemons’ character executes another Asian journalist—who, of course, was also introduced five minutes prior for the explicit purpose of being sacrificed to some attempt at a statement on American racism—for the crime of being from Hong Kong. The tense vignette ends when the gunmen are hit by a car driven by the only Black journalist, conveniently absent for this exercise in racist interrogation; the Black journalist dies anyway. Leaving aside the crassness of introducing two non-white characters as sacrificial lambs, the scene is both an exercise in tension-building and a tremendous directorial failure. Rather than accidentally make a statement about the forces at play even on the most basic level—acknowledging, in other words, the fact that anti-Black racism is the sine qua non of American reaction and that a civil war, like the one that happened in real life, could not emerge without this racism as animating force—Garland indulges a convenient and cowardly instinct: get just close enough to real life to permit the audience to project their own meaning, then speed breathlessly away to the next cutscene.

A friend describes Civil War as Playstation-core, which is instructive both in the sense that many of its marquee scenes are shot like Call of Duty cutscenes and in the sense that its viewers are afforded only a facsimile of interpretive power. Like many a video game, it both provides its thrills and also leaves you wondering, at its end, how you just spent that much time in a dark room without doing anything. It’s a mode, of course, at direct odds with the film’s vision of journalism. The film’s journalists are portrayed as thrill-chasing public servants, motivated by something between self-aggrandizement and humanitarianism to capture the worst of mankind and deliver it back to the masses to interpret. But where Garland pays lip service to the power of interpretation, his film devalues the endeavor completely. The film references no internal audience who will actually receive its photographs of war crimes and presidential executions; these journalists risk their lives to preserve images, but it’s not clear for whom. The work of interpretation, both within the film’s universe and in our world, is left for someone else to figure out.

Perhaps we’re meant to leave Civil War convinced, at the most mediated time in human history, that there aren’t enough images in the world. But it’s hard to watch Civil War in the current moment, in which America bankrolls a nation that is killing both journalists and civilians forced to become journalists to document the atrocities being committed upon them, and take the idea that journalists can save the world seriously—or, worse yet, that they must wage war against context in pursuit of objectivity. It takes context to understand how the people with actual power got the guns, and it requires interpretation to determine whether they should be allowed to have them. Civil War is capable of neither.