Dispatch: Never Hungover at the Barclays Center

On a night where I could've been anywhere, I saw the Nets play the Pistons

I’m in my parents’ basement, home for the holidays, finger hovering over the “confirm purchase” button, preparing to consummate the frankly Satanic Christmas gift my youngest brother and I have devised for each other, an agreement to split tickets to see the reeling Brooklyn Nets take on a Detroit Pistons team in the process of setting the NBA record for a single-season losing streak when I’m visited by a moment of intense remembrance. I became a Nets fan in large part due to cheap tickets—Groupon packages, $25 for a hotdog, a ticket, and a meet-and-greet with Anthony Morrow, sub-$10 tickets to the Prudential Center, my brother and I gorging ourselves upon truly pitiable basketball with the money I’d earned from waiting tables. My journey with the Nets, like many within the small circle of the afflicted, began with a simple premise: why not, at this price? I fell in love with a team that had nothing to sell me but cheap tickets and a pie-in-the-sky vision of future success prompted by a move across state lines. Pressing buy against this surge of memory was materially different (namely, about five times as expensive) than it had been in the past, but these discrepancies couldn’t distract me from a revelation: we were traveling into the belly of the beast to see a New Jersey Nets game that would only incidentally take place in Brooklyn.

Our tickets were not discounted through a rare moment of good-naturedness from the blog’s greatest enemy, billionaire moralist and lacrosse-booster Joe Tsai, but because of the circumstances. The Nets had just returned from a West Coast road trip during which they officially came out, to anybody who bothered to stay up and watch their losses, as a bad team. The night before the game, they’d hosted the defending-champion Denver Nuggets, the sort of draw that any sensible person electing to watch Nets basketball on Christmas weekend would choose over what would follow. Where the Nuggets game would at least promise an opportunity to witness the best basketball player alive and presumably enjoy high-level play, the Pistons game offered a sort of demonic polar opposite. The tired, free-falling Nets hosted the historically terrible Pistons in the first tilt of a home-and-home back-to-back series that every Nets fan fundamentally believed would result in the Pistons finding their first win in more than 25 games. If professional organized sports as a multibillion-dollar entertainment industry operate upon the fantasy that winning intrinsically matters, this game was a glitch in the matrix, one in which the sole purpose for both teams was to avoid a humiliating loss. I couldn’t have imagined a finer way to spend my Saturday night.

Commuting to a Brooklyn Nets game, especially if you’re wearing Nets gear, gives one the sense of total invisibility. In The City & the City, China Miéville sketches a portrait of Beszél and Ul Qoma, two cities that occupy the same geographic space but are rendered their own through the practice of “unseeing”—the obligation forced unto each city’s respective citizens to ignore and forcefully forget any evidence of the other city’s presence. So it is that you, as a Nets fan, are rendered a spectral figment approaching the Barclays Center on the subway. Your Mikal Bridges jersey or Brooklyn Nets hat slips unnoticed into the throng of people commuting home from an exhausting day of work, the upwardly mobile professionals on the way to a wine bar, the masses wholly disinterested in and unaware of the team that has made their conversion into fans a do-or-die mission. You can try, if you insist, to scope Nets insignia out amidst the human movement, but doing so requires the exact level of unseeing everybody else that you imagine is being done to you. My brother and I enjoyed a tremendous burger at Walter’s, which despite being a ten-minute walk from the Barclays Center felt a world away.

The first thing I noticed upon filtering into the line to enter the stadium was that almost nobody around me spoke English. The people who did seemed, most often, to be on early dates. If you find yourself wondering how the Nets could announce a sell-out crowd on a Saturday night game against the Detroit Pistons, the answer appears to lie in the near-universal, often naïve instinct to have a “nice night out in New York City.” If the Brooklyn outside of the Barclays Center was disinterested, that within it could at best have been said to be passively interested—people who had been told, at some juncture of their lives, that it would be fun to see a professional basketball game. The utter indifference of the people around me only helped to contribute to my experience of the Barclays Center as liminal space. Against this crowd, the real, independently motivated Nets fans wore their own mark of the beast, leprous figures doomed to care deeply about this ultimately meaningless game that everybody around them would forget the moment they left the stadium, if not sooner.

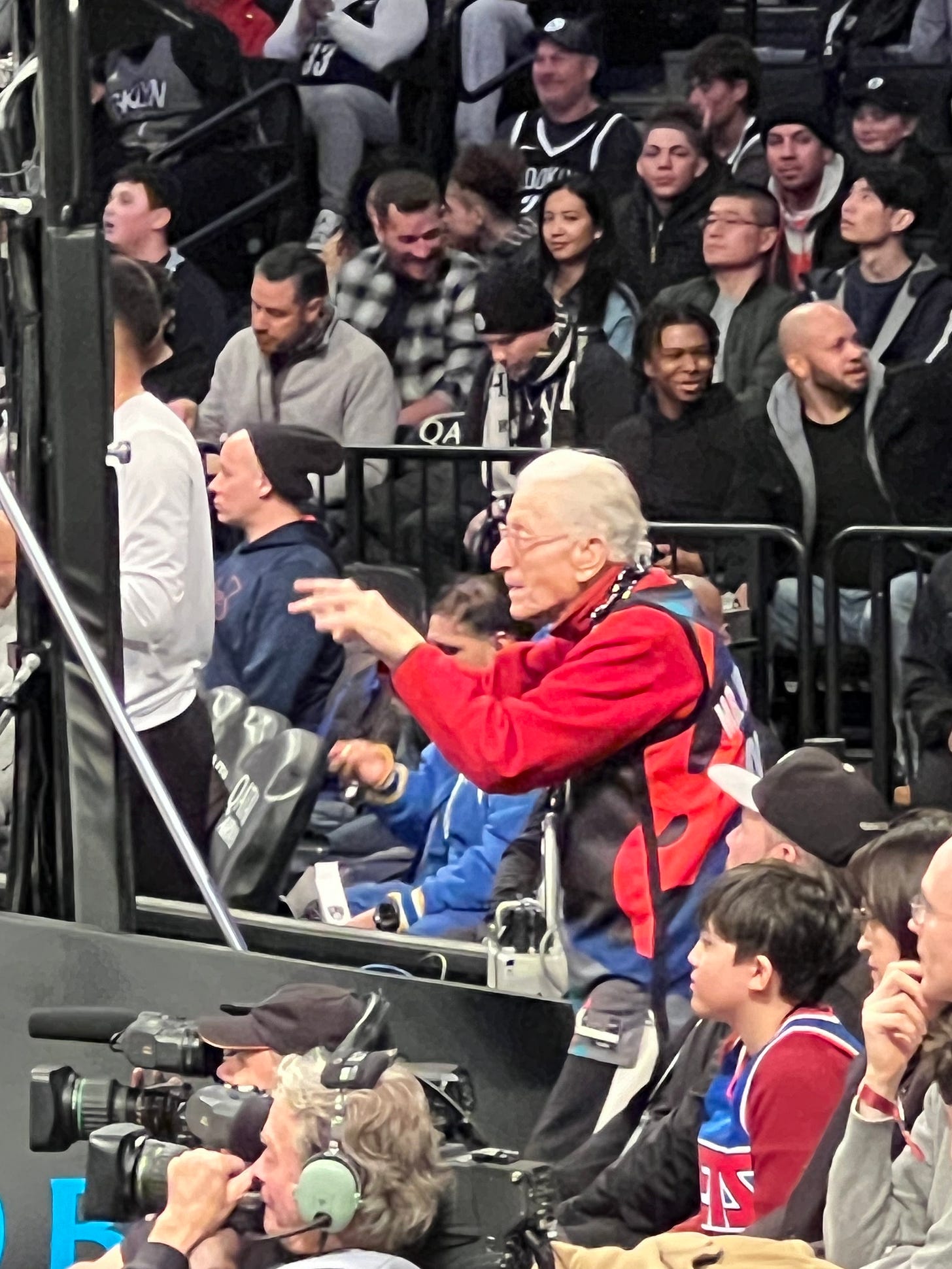

After walking past the in-arena facsimile bodega (an installation that I’ve confirmed after the fact was not a delirious figment of my imagination) and a foyer DJ transitioning “A Milli” into Taylor Swift’s “I Knew You Were Trouble,” my brother and I arrived at our seats. It being Nets vs. Pistons, we quickly scurried to better ones—the sort of seats where you can read Mr. Whammy’s every expression, where Dorian Finney-Smith can theoretically hear you if you yell to him at the right moment, where you and your brother can wonder aloud whether Cam Thomas might not suffer from clinical depression. Nic Claxton was handed the microphone to give a brief, fairly disastrous speech in honor of NBA Cares month, during which time his teammates laughed. Cheerleaders danced in Santa suits. It was Christmas time, and the game began.

As someone who places at least some premium upon my mental health, I had up until this night never watched a Detroit Pistons game. As such, it was my first opportunity to lay eyes on the team in the process of making NBA history for losing—a sort of history that, as a Nets fan who endured a 12-70 season, I feel deeply attached to. I had expected an atrocity exhibition, which, outside of the play of Jaden Ivey, I did not receive. While the game veered into its moments of degeneracy—Isaiah Stewart, pornstar Kendra Lust’s favorite player, hitting three straight threes being the prime example—the Pistons presented themselves mostly as a team that was thoroughly unremarkable. Cade Cunningham, who for 24 hours unseated Anna Khachiyan as the person in New York City most hated by Twitter users, looked anywhere from serviceable to good. Rather than feeling that I was watching history, I settled into the deeply familiar comfort of watching simply another mediocre Nets game.

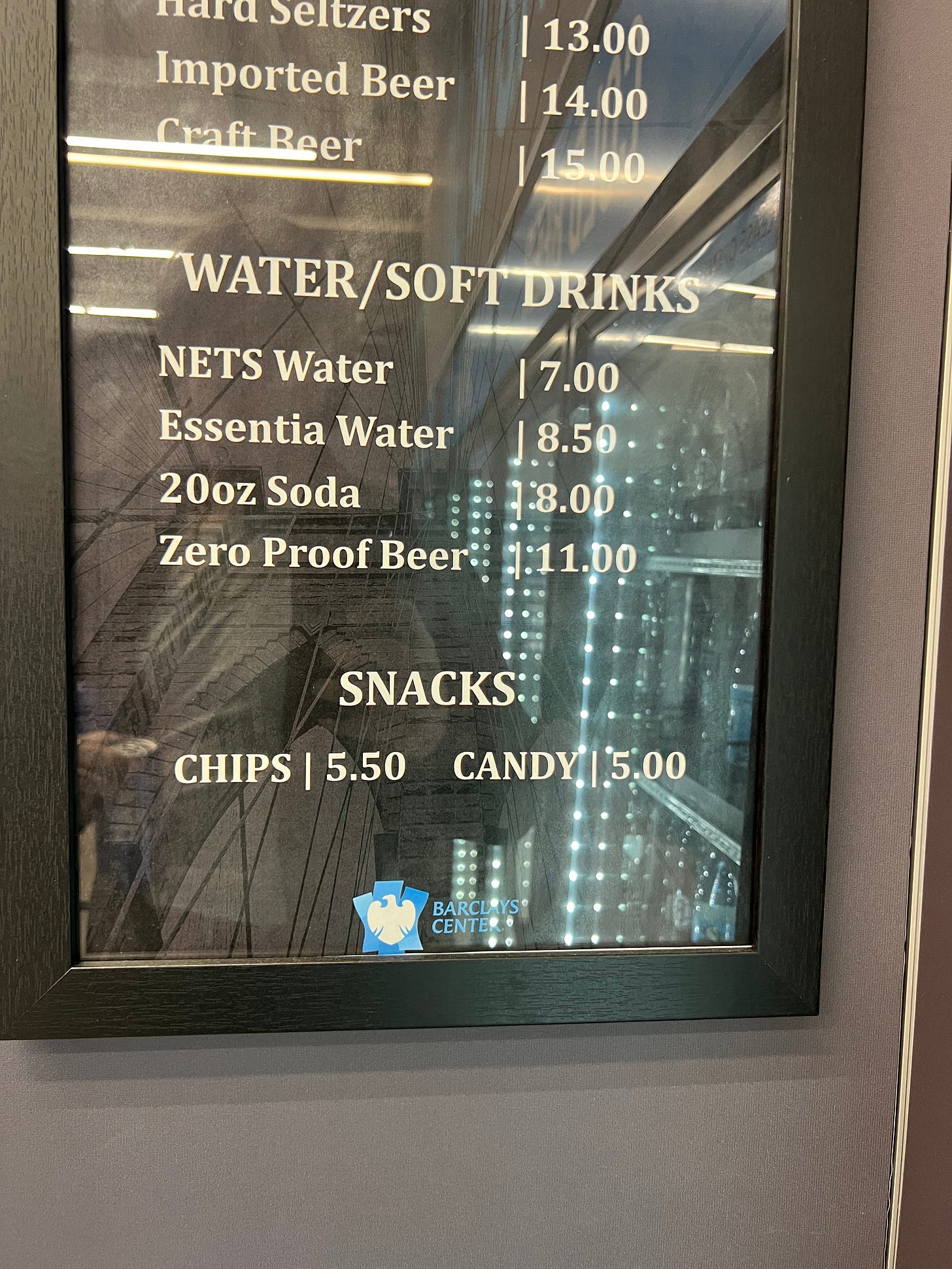

The people around me, too, appeared at home amidst this mediocrity. What, I wondered, could the binding thread have been between the people around me? To my left, a lovely young couple whom I realized, after three quarters of polite seatmate charades and gestures, spoke little to no English. In front of me, a family of five, at the game because the father got tickets through his company. “I’m here for the food,” he texted a friend, clarifying that his company would not cover drinks. Aside from the food, the only thing that could tear his attention from his fantasy football team, “Doug’s Gator Nation,” was fellow Florida Gator Dorian Finney-Smith. “That’s Finney-Smith,” he would periodically remind his wife, “from Florida.” He told his friend that his son, Madden, was enjoying himself. Just in front of him, a young woman in a mink hat took a barrage of selfies with a selfie-light panel attached to her cracked Samsung phone. To her left sat a group of ambiguously Baltic tourists, one of whom wore what appeared to be a national soccer team jersey. At one point, another crowd member recognized his jersey and exclaimed something in another language; my neighbor made what my brother identified as a nationalist hand gesture before timidly sitting down.

Excluding my brother and myself, there was only one person in my immediate vicinity who could stake any claim to being a Nets, or basketball writ large, fan. He, a young father, was in the process of converting his son into the second. Hearing this father teach his son when to cheer, who to root for (in this case, Day’ron Sharpe), and what deserved his attention, I was overcome by a wave of emotion. Perhaps this was just a night where I’d been primed for sentimentality. During timeouts, children were brought out to halfcourt to participate in a game in which they stuff as many Christmas gifts as they can into a Santa-coded sack; at one point, the Nets honored Joe Harris with a tribute video that felt far more like a late-stage A24 film than an homage to a professional basketball player. Still, this ritual of fatherhood and social reproduction moved me to no end. Nets fandom can so often feel like being mired in a recursive cycle of suffering—the tickets creep more expensive, but the failures remain inevitable and ever-intensifying. Whether in New Jersey or now, the Nets were again a team that could only be said to have a future in terms of the most unbearable abstraction. And yet here was a child whose first basketball memory would be a game where his father interrupted his lessons about basketball to scream “get that shit out of here” at a Nic Claxton block, who would get to choose not between LeBron James nor Kevin Durant nor Steph Curry but Mikal Bridges and Cam Thomas for his favorite player, who would maybe never care for basketball or the Nets but who just as well could.

In the time between my attending this game and writing about it, the online Nets fanbase, which is to say the only real fanbase, has devolved into a full-throated civil war. The Nets have revealed themselves as a group only capable of beating teams gripped by record-setting losing streaks, an unwelcome turn that has exposed the fissures of the entire apparatus of Nets fandom. NetsDaily, the lodestar of the online fanbase, has tweeted the sort of half-wistful, half-death-fearing musings that would be funny if not for the reality of his advanced age. The team’s lack of direction has pitted institutionalists, who have bought the front office regime’s pleas for patience and fetishizations of “flexibility” wholesale, against a cadre of anti-management, pro-hooper malcontents who have determined that Cam Thomas is not only the team’s only hope at a competitive future but is also something like a political prisoner. Each loss begets more negativity, each turnover a new appeal for a different player, coach, or figurehead to be properly identified as the cancer plaguing the Brooklyn Nets. A season that always promised mediocrity has begun to deliver, and it is driving legions of fans insane.

I think, as I scroll Twitter, of the young kid sitting behind me at what was otherwise a wholly unexceptional Brooklyn Nets win. Where nearly everyone else around me was definitionally transient—foreign tourists, disinterested dates, comp-ticket redeemers—or one of the unenviable few who have actually come to invest meaning in Nets basketball, this child alone seemed to have a choice. The experience of sitting not courtside but close enough to read every expression in Dennis Smith Jr.’s pleas to referees could turn into just another in a series of childhood memories for this kid; such would be the logical path. And yet, wasn’t there a world in which that night saw a real life Brooklyn Nets fan born? Aside from ticket prices, in-arena production value, and the lack of a meet and greet with transient role players, was there anything substantially different between his experience of enjoyable yet underwhelming basketball and mine, so many years ago? What I mean to say is: does this kid have a choice, and did I, or is allowing your emotions to be partially regulated by the failures of a franchise whose key constituents do not know you exist something that just happens to you? Is there anything more to this unfulfilling, yet inescapable attraction than time, place, and the opportunity to see a discounted game?

The Nets won 126 to 115, behind Mikal Bridges’ 29 points. Pistons coach Monty Williams called the loss “hard to swallow.”

This is terrific, as always. I was also at this game and was bemused to see the Brooklyn Nets Barbie boxes reused for the holiday performance, as I’d seen them in a Brooklynettes performance from the Raptors game

i thought i was a true pistons sicko but even i have the self-respect to have a different favorite player than beef stew (excellent piece, btw, nailed how i always guessed barclays center felt)