Thanked The Sensei Again Award

A blog about One Battle After Another

Preliminary business:

Don’t watch regular season baseball anymore—unsustainable once you get an email job—but the mere thought of the Boston Red Sox dredges up a therapy-resistant level of animosity in my heart. May God watch over the New York Yankees.

Geese album: good despite being recorded in Los Angeles. No small feat. Lost in the shuffle: great new Cate Le Bon record, Nick León back on NTS…can’t bring myself to listen to the Young Thug whiteface album.

The Louisiana State University Tigers…what’s left to say? Disaster. Meanwhile, I will be attending Giants-Saints this weekend in the Rob Lowe NFL hat.

Now, a blog (conditioned by the caveat that said blog concerns details about the plot of One Battle After Another):

Thanked Sensei Again Award: Considering One Battle After Another

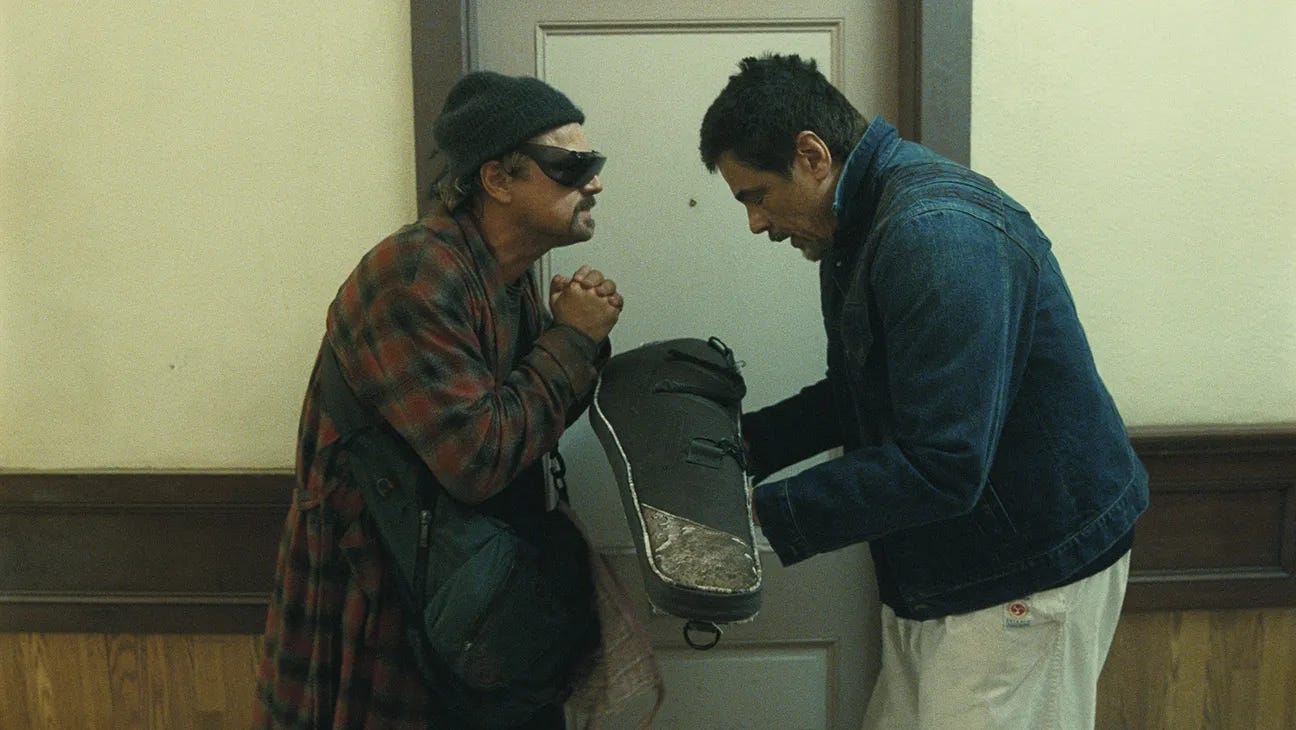

My favorite sequence in One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s newest Pynchon-indebted triumph, comes about halfway through the movie. Bob, née Ghetto Pat, the ex-revolutionary “drug and alcohol lover” directorial stand-in, rages on his still-charging cell phone against a tight-lipped new-gen radical. His anguish, played hilariously by Leonardo DiCaprio at the height of his powers, steams from his inability to remember a sequence of code words that will get him to the safe-house toward which his daughter, Willa, is speeding with a group of French 75 militants. As Bob sputters and screams, the effortlessly cool Sensei Sergio (played, in the sort of turn I will never forget, by Benicio Del Toro) manages to find him a gun, talk him down, usher a group of undocumented families away from an impending ICE-style raid, and crack a Modelo. Willa, meanwhile, is being whisked to ostensible safety after placing her trust in a complete stranger who happened to know a series of code words the importance of which were impressed upon her by her father. Sensei models his radicalism with concrete acts of service; Willa places her utmost trust in the teachings of her ex-rad father; Bob sits on the couch and screams until he’s finally asked a question about pussy.

Is Bob a laughingstock wash-out? A cautionary tale about the pitfalls of radical action? A manifestation of the latent conservatism one typically associates with aging? Or is he, like countless would-be radicals before and after him, just a guy who followed his dick until he was in a bit over his head?

A lot of hay has been made about the politics of One Battle After Another, specifically as to whether it’s a sufficiently “radical” blockbuster. This conversation was tired before it even began—and should have been put to bed by sam bodrojan’s sharp rejection of the premise in her review of the film. Of course, the $175 million budget film distributed by Warner Brothers through a campaign involving an official Fortnite crossover was never going to be Battleship Potemkin; docking it accordingly feels more like a failure of imagination than a piece of savvy media criticism. And yet One Battle After Another feels both like a miracle and a masterpiece precisely for the way that it engages with the political rather than limply smuggling it in through the abstract and the allegorical.

At risk of stating the obvious, One Battle After Another is borderline inconceivable. It’s insane that Paul Thomas Anderson directed a big-budget comedy-action movie; it’s insane that said blockbuster is in any meaningful way indebted to a Thomas Pynchon novel; it’s insane that said movie’s plot revolves around a betrayal made by an obvious Brace Belden analogue; it’s insane that the Best Picture frontrunner depicts ICE raids and extrajudicial killings as the bored trappings of a horny and resentful Nazi cabal; it’s insane that, like, my dad is at the movies watching this right now. And so, while no, of course One Battle After Another is neither politically radical nor “revolutionary,” it is something far more compelling: a propulsive, expertly-crafted thriller about the pain and joy of loving people in a time where evil has conclusively won the day.

Enough people have written about the plot of One Battle After Another (and conventionally reviewed it) well enough that I won’t bother with my own summary. Go ahead and read the great reviews from Sam (linked above), Paul Thompson in Pitchfork (still makes me giggle), Adam Nayman for The Ringer, and PTAMuse Eddie Averill over here on his blog; they do all that exceptionally well. Instead, I’ll just go mid-to-long on a few particular areas of interest in the best movie of the year.

One Bamba After Another

It was hip for a while to tweet about how PTA, along with his cohort of exclusively male “masters of the craft,” has never filmed a picture with iPhones in it. This sort of stuff is perfect for Twitter—Lindyman gets to pontificate, pablum merchants spew about the aesthetic degradation of our times, everyone eats good. Of course, One Battle After Another embraces modern technology to the point where iPhones advance major plot details (including, at the film’s end, a Certified Unc Moment during which Leo’s Bob can’t really take a thirst-trap selfie). Old news.

More striking to me is the fact that this is the first film I’m aware of to count among its needle drops both Sheck Wes’s “Mo Bamba” and that “Shut Up And Dance With Me” song (wedding music). It’s silly, it’s vaguely “of the times,” it made me bolt up in theaters, all that. Walk with me, briefly, for a crazy dumb guy theory. “Mo Bamba” and “Shut Up And Dance” comprise half of the film’s proper soundtrack inclusions, punctuating a truly outstanding score from Bad Guy Jonny Greenwood. The other two, Steely Dan’s “Dirty Work” and Tom Petty’s “American Girl,” are equal parts rousing and thematically apt. They both operate quite literally (not unlike, say, the needle drops in The Summer I Turned Pretty): “Dirty Work” to evoke the bittersweet tedium of Bob high out of his mind at a parent-teacher conference, “American Girl” as a sort of uptempo send-off for the newly-minted radical Willa on her way to some direct action. We know, then, that PTA views as part of his craft the intentional selection of songs with both musical and lyrical pertinence to the scene at hand; we also, from the casting inclusions of Alana Haim, Dijon, Teyana Taylor, and Junglepussy, know that PTA is relatively tapped in. Is it impossible, then, that at some conscious level Anderson chose to soundtrack the school dance with “Mo Bamba” to set up the major plot point of hoes (inclusive) quite literally calling Willa’s phone? Stupider yet, is it so impossible to imagine Anderson intentionally scoring the moment in which Willa puts her trust in a complete stranger with the kitschy and stupid “Shut Up and Dance?” I’ve grown somewhat obsessed with this line of inquiry for the tremendous possibility it suggests: if Anderson truly is this much of a Dumb Guy, and is nevertheless capable of operating at such a transcendent level, then what’s stopping you or I from creating something beautiful too?

The Vineland Question

One Battle After Another is, unlike Inherent Vice, far from a direct adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland. That’s a good thing—Vineland would only work as a television show, and I wouldn’t want to watch the prestige Vineland show, and Vineland is TV-and-movie-skeptical enough as is. People are having fun debating the extent to which One Battle After Another is or is not sufficiently Pynchonian (points docked, as Max Read aptly observed, for the overly literal protagonist names; points added for, in no particular order: the casting of a person named Chase Infiniti, the skateboarding guys, the banana pancakes nod, Sensei’s whole shit, the kid being named “Bluto,” the chicken store name…), but the more interesting question is where, exactly, the film diverges from the inspiring material.

Anderson, of course, borrowed the general parental dynamic and broad plot points from Pynchon—with, depending on who you ask, either cosmetic or meaningful alterations to the plot’s temporal setting and the cast’s racial composition. One Battle After Another’s most fascinating divergences, though, come in the form of the custodial love triangle. Unlike in Vineland, the film’s mother figure (played by a steely and brilliant Teyana Taylor) is entirely absent from the modern-day plot; rather than hunt her as the book’s authoritarian Brock Vond did, Sean Penn’s Sgt. Lockjaw seeks to destroy any trace of their coupling by killing her daughter. It’s the sort of decision that clarifies the plot’s stakes for Anderson—transforming a politically-charged custody battle into a life-or-death rescue mission—but also sacrifices something meaningful. Vineland is a novel, among other things, about the seduction of square, fascist life: hippies sell out, revolutionaries work for the man, and the government wins less by force than by all of its opponents simultaneously deciding to throw in the towel. Vond, The Man’s personification, makes his claim that he is Prarie/Willa’s father, but seeks to possess rather than destroy her. The effect, of course, is that Prarie finds herself, like her mother, seduced by the uniform and calling out for Vond.

In One Battle After Another, Willa is afforded far less familial agency. Of course, in the film’s penultimate sequence, she stirringly chooses Bob as her father, it’s not like she has much of a choice; the guy that the DNA test purports to be her dad is a roided Nazi who tries to kill her and talks like RFK. If I had to guess, I’d imagine this choice was made in the spirit of plot economy, though it’s not impossible that Anderson was more interested in telling the story of a young Black woman trying to navigate a nation that both claims and attempts to kill her. And, yes, the discursive fallout would have been a disaster if Anderson decided to portray the fascistic wing in this film as seductive in any way. Still, it’s a decision that foreclosed a potentially more interesting film: one in which Willa is given the power of choice rather just her admittedly useful knack for survival. One Battle After Another’s personal-as-political ending, in which Willa drags her pot-smoking dad into modernity as he places his faith in the future in her, is both sweet and earned. But haven’t you heard? Assuming that the kids will be alright is so 2019. There’s a palpable irony in Anderson updating the tenets of the 90s Pynchonian blackpill just to elude the most salient question that the book has for us today: why are all the kids suddenly fucking fascists?

Your Being Manipulated

I’ll admit it: it saddens me to see people discard Eddington like Woody in Toy Story now that the ostensibly competent Political Movie is out. My friends, you can have it all. Eddington is a deeply flawed but ambitious film about politics; One Battle After Another is a marginally flawed pop art masterpiece informed by politics. They’re doing different things and work for different reasons—"Firework” wouldn’t have worked in one, “Mo Bamba” wouldn’t have worked in another, if you want to get down and dirty about it. Eddington would be gibberish if not for its ability to spam references about things that just happened, where One Battle After Another could, more or less, have been about anything. Plenty worse versions of the film are churned out every year—movies in which our protagonists find themselves in outer space, or fighting supervillains, or whatever the hell else. One Battle After Another is exceptional in no small part for its evoking, for instance, the brutal cruelty of ICE raids and abductions, but it does not depend on its timeliness to work. If it did, it would be just another mid blockbuster. The movies can be put in conversation, surely, but only up until a point. Neither, as far as I’m concerned, disproves or diminishes the other.

Sensei Apology Form

In my last blog, I complained briefly about the emergent phenomenon by which people feel extremely comfortable expressing strong, jilted opinions about the decisions made by major corporations. Chief among the list of behaviors I was whining about was the widespread disdain I observed for One Battle After Another’s marketing campaign. Allow me to offer a rebuttal.

In New Orleans, summer is its own authoritarian regime. You shower twice a day and thrice if it is a weekend; often, you feel so tired that you cannot lift your fingers to Google “Iron deficiency signs.” When you drink beer, you sweat faster than your body is able to even receive its toxins, suspending you in a state of dewy futility like a seagull coasting in place amidst a strong gust. There is nothing to do but go to the movie theater. This summer, every time one went to the movies, they were treated to the exact same trailer for One Battle After Another (I saw the second, more action-y trailer only once, at an AMC, before The Naked Gun). Accordingly, I know every word and beat to the One Battle After Another trailer. My girlfriend and I began using “Thank You, Sensei” as a shorthand for sincere gratitude before we even knew of the film’s release date. If anyone is qualified to have an opinion on the One Battle After Another trailer, I am.

My verdict: the tonally inconsistent, unremarkable trailer works perfectly to advertise its film, and you all need to be more grateful. For those who allowed themselves to appreciate, rather than despise, the One Battle After Another trailer, the entire film felt like fan service. When Sensei Sergio (the moral center of the film, that’s another blog, but put a pin in it) appeared on screen during the “Dirty Work” montage, my girlfriend and I tearily grasped one another’s arms and whispered “that’s Sensei.” When Bob and Sensei Sergio walked into the apartment building hall at the center of the film’s best scene, we bolted upright and louder-than-whispered: “that’s the ‘Thank You Sensei’ Hall!” Don’t get me started on the payphone.

Having been bludgeoned to death by the One Battle After Another trailer deepened my appreciation for actually seeing the movie in a way that I can hardly put into words. I’ve tried my best at it, and will stop shortly. Some parting ones: it’s a funny trailer for a hilarious movie, it piques your interest without revealing the plot, a lot of you need to take a load off, and I will sincerely miss seeing it each and every time I begin to feel that indescribable feeling we get as the lights begin to dim.

about time somebody sounded off on school dance Mo Bamba

Great blog. The bit about Vineland was fantastic, I completely agree (and also loved the movie). The whole point of the book is the choice and the seduction, which is basically absent in the movie. But is there a way to read the ending that's not entirely optimistic? That Willa isn't actually choosing freedom any more than Bob did or has?