Rap, Capital; or, Where did the coyotes go?

On Joe Coscarelli's Rap Capital and the end of an era

There are not many apparent reasons to remember Follow the Leader, the short-lived 2016 CNBC program in which a host spent “72 hours embedded in the life of a different superstar entrepreneur.” Yet, as if by a happenstance so perfectly congruent with the ephemera of the rap music reverberating throughout the waning pre-Big-Streaming Internet, Follow the Leader captured a one-minute clip that can only feel, in retrospect, like a skeleton key to the end of an era.

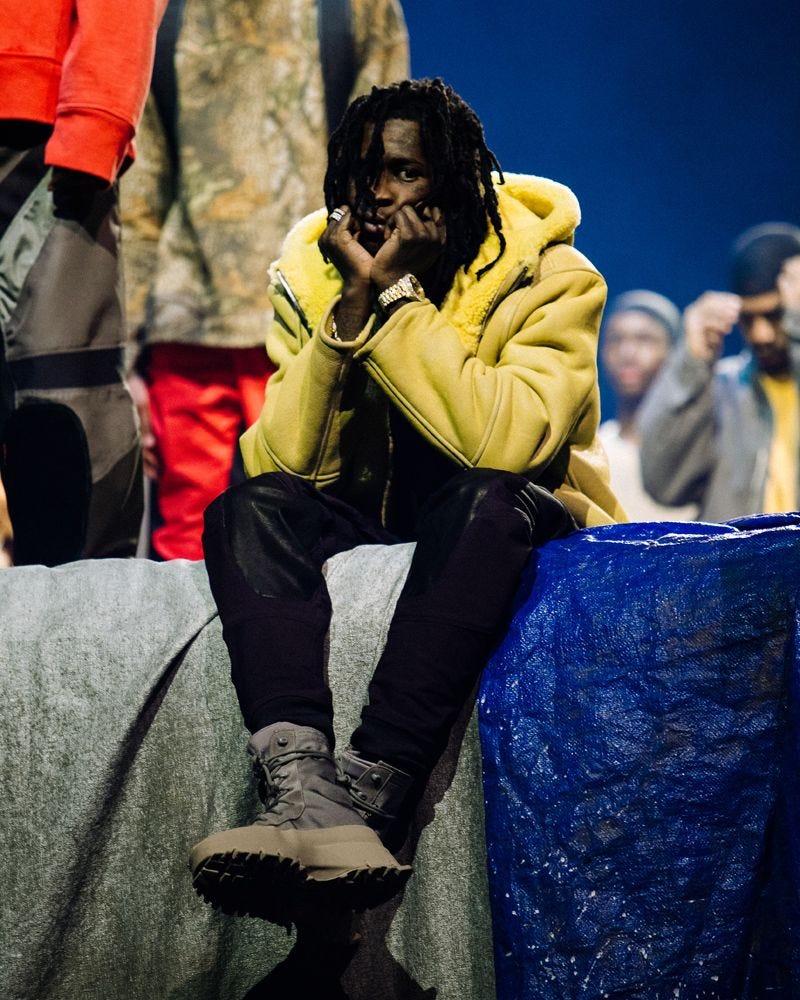

In the clip, Lyor Cohen – the co-founder of 300 Entertainment and the now-Global Head of Music at YouTube – admonishes Young Thug, his label’s warbling, outré star. The pair stare each other down across a suffocatingly bland white table, surrounded by Chinese evergreens and ashen-faced executives. “I understand that you’re shy, and you don’t like doing it,” Cohen begins, “but the fact of the matter is your fans actually want to hear from you.” Thug perks up, perching upon the edge of his seat and toward a bottle of Sprite and a plate of unidentifiable food: “I don’t need to! Motherfucker, I don’t want everybody just to know,” he protests, launching into a noticeably (and perhaps quite justifiably) disdainful impersonation of an imaginary fan. “Oh,” Thug mocks, “we know!”

Moments later, in a rejoinder so nonresponsive to Cohen’s lecture that it must be the byproduct of a quick cut by editors, Thug announces that he wants 10 number one singles on the year. Cohen reacts like a teacher ready to turn his student’s rebellion back on him. “Okay,” he responds testily, “if you don’t freestyle, and you actually work on the singles, and record great choruses, and develop your songs, yes. You just record so many songs and leave them like little orphans out there. Okay?”

But Cohen appears to misunderstand what makes Thug tick. Rather than express shame, Thug responds proudly to Cohen’s characterization of his creative process.1 “You have to come back to them!” he admonishes Thug regarding his songs. Thug cuts him off: “No, I don’t. Hell nah, you . . . the critics come back to ‘em!”

It’s possible to divine, with some level of accuracy, when this conversation took place due to the upcoming projects that Cohen mentions. Cohen refers to two albums on the horizon – Hy!£UN35 and Slime Season 3 – that would come to loom large in the mind of fans of the then-most-exciting rapper in the world. Hy!£UN35 (a stylized spelling of Hi-Tunes) the promised album that never came, Slime Season 3 the album that came twice: first as February 2016’s “I’m Up,” then by its proper name in March 2016. These three records, the two actualized, the one forever mythologized, would come as a splash of water to the face of listeners enamored with Young Thug’s unbridled, galaxy-bending stylings that had up until that point appeared ready to burn rap’s mid-2010s pretension and rigidity to the ground. Alongside the year’s two thuds from Thug’s frequent collaborator, running-mate, and peer hell-raiser, Future (his in the form of 2016’s disappointing Purple Reign and dreadful EVOL), these records were a grim pronouncement. The run is over, they said at their worst; these luminaries are human, at their most generous. In retrospect, the answer sat somewhere bleakly in the middle: the market had been oversaturated.

If the infamous Follow the Leader clip memorializes the moment when the Atlanta rap scene’s manic burst of creativity gave way to a more cynical, corporatized market-flooding, then Joe Coscarelli’s excellent Rap Capital: An Atlanta Story is a long-overdue deep dive into the industry machinations of the most important music city of the last decade. In Rap Capital, Coscarelli tells the story – or, rather, interweaves a number of stories – of Atlanta rap from the years 2013 to 2018. These were the years, as Coscarelli well-explains, that Atlanta rap exploded from a peripheral force to the driving, generative seat of creativity and cultural capital in 2010s music. Atlanta broke the hegemony, then expressed through DJ Mustard’s two keys and back-tracked “hey”s. Trap became king – even Ariana Grande talked her shit over snares and 808s.

Tasked with charting Atlanta’s rise from outsider to hegemon, Coscarelli is wise to focus predominantly on Quality Control, the imprint housing Migos and Lil Baby among others. Quality Control did not by any means birth popular Atlanta rap or deliver any of its most creative and magnificent, but it did corner the market; it’s Quality Control, more than any other label, that made the Atlanta sound, influence, and aesthetic ubiquitous in the late 2010s. The label and its artists are also fitting vessels to illustrate the angle laid out fittingly in Rap Capital’s title: not just how Atlanta became the headquarters of culture, but also how capital – cultural, and financial – came to reward and then dictate the terms of the Atlanta scene’s creative frisson.

In rap, as in life, capital dictates the terms. Rap, as Coscarelli notes, has always intersected closely, and often orthogonally, with capital. Rap is the music born out of capital’s cruelty and artificial scarcity - of the failures of capitalism as such. Rap is music from the underbelly, art created by the people whom capitalism sacrifices to the altar of endlessly hoarded growth, whom capital exists in a relationship of extraction and exploitation. Rap’s popularity, then, sells this outsider experience (there’s almost nothing more important in rap than authenticity). At its most popular, though, rap can be a medium of capital excess: flexing from the elect who made it through, ostentatious and boisterous braggadocio from artists for whom the right to talk shit has been hard-earned. And so a bizarre relationship, where rappers are permitted to (and often are handsomely rewarded for) voicing the most grotesque flourishes of capital accumulation, permitted to do so for their ability to testify to its failings and atrocities. A bind emerges: rappers are expected to, and are celebrated for, both having and not. Their success requires a specific duality and a well-tuned receptivity to trends, shifts, vibes, and waves.

If the book’s narrative center is Quality Control, its rapper protagonists are Lil Baby and Migos. Coscarelli charts their careers from humble origins to world-beating superstardom in a captivatingly breathless narrative. Even as tragedy looms large (the most obvious, but by no stretch the only, being Takeoff’s death this year), Coscarelli’s book is a thoughtful and tightly written epic. His focus on Atlanta’s commercial winners is not exclusive; some of the book’s most captivating portions detail the stories of runners-up, from Lil Reek to Marlo, souls destined to occupy rap’s burgeoning middle class.2 Still, one cannot but notice that the story Coscarelli tasked himself with telling treats as peripheral the two artist who, by my estimation, were responsible for the gold standard of Atlanta’s mid-2010s boom: Future and Young Thug. Future and Thug appear in the book, and Coscarelli sings their praises, but their names are most often invoked to create a certain mise en scène. They are rappers who have prodigies, connections, crew members, and influences. Their music is less celebrated, their stories largely untold – the major exception, of course, being that the book ends with Young Thug’s federal prosecution on nonsensical, racist charges.3

These exclusions do not read as disses from Coscarelli, and they do not undermine his work. He tells the story he has reported on in the way that makes sense to him. Still, while Coscarelli does not hold himself out as a music critic, it is mildly deflating to read what – for good reason – appears to be the definitive tale of mid-2010s Atlanta rap with only cursory mention of its creative pioneers and, by my estimation, artistic titans. Young Thug and Future’s creative peaks were more than just contributions to a broader scene: they were world-stopping, generational, canonic feats. They contained in them an indescribable and felt sense of promise.

I read Rap Capital, then, as a book about how these moments ended as much as how they came to be. Rap Capital is among other things a business book, or at least a capital analysis. Migos, of course, were part of this generative boom as well. Their earliest, hungriest work – “Versace” and “Hannah Montana” the strongest exemplars – were bristling, joyous, wholly unconventional works. They pissed people off before they burrowed themselves into complainers’ brains, making converts out of curmudgeons. They were imperfect, uneven, deeply stupid, and wholly alive. But so, too, does Migos stand as the embodiment of the uninspired oversaturation that would come to make this moment in rap feel like just another trend, strip-mined of all its generative essence and sold for its component parts. Atlanta rap was everywhere largely because Migos was everywhere, and being everywhere meant phoning it in – lifeless Quavo verses, lazily autotuned choruses, ear-grating obligatory guest spots on pop songs. Migos represented the creative ouroboros: the feeling that this revelatory music could and should be everywhere, paired with the sinking realization that “everywhere” turned out to be a Sprite commercial.

Rap Capital is worthwhile not only because it charts this path to oversaturation, but also in how it details its machinations. In one of the book’s strongest passages, Coscarelli sits in on studio time with the Migos:

To watch the group in the studio was to witness a start-and-stop relay race that was also a magic trick. No one seemed to be exerting themselves all that much, and yet by the time they neared the finish, everyone but the rappers was exhausted and dizzied and unsure of how they’d ended up where they had, having heard the same few bars of music repeated for hours.

In practice, there is no actual writing going on while Migos writes a song. Their style of rapping—eons away from the old-school idea of a guy with a pen and a pad—was learned from their idols, like Gucci Mane and Lil Wayne, who freestyled at will. But instead of coming up with lengthy stanzas in their head and then rapping them in full, à la Jay-Z, the Migos members craft songs directly into the microphone, one syllable and then one word and then one phrase and then one line at a time—starting, stopping and rewinding over and over again, until there is something resembling a verse.

This method is detailed through an example:

On this day, Quavo took the mic first with no discussion, his voice soaked in a light, echoey Auto-Tune effect, making him sound like a lovelorn, short-circuiting AI creation. At first, he multitasked, rolling a blunt in the booth while feeling out the beat with his mouth, mixing gibberish sounds with a magnet-poetry grab bag of Migos keywords: “Ride…Ehh, ehh . . . Uhhh, uh, uh, uhuh . . . I got fifty K on me . . . Extra . . . Serving fiends, my dog . . . Eeeaaaaaaahhhhh. Ay! Uh! Yep. Yessssiiiiiirrrrr. This is . . . Ride. Up. Vibe. Drop-top. You dig? Dah, dahdahdah . . . Ay. Ay. Ayyy. Riding in that . . . drop-top. Miiiigooos. Big dogs.”

The other guys barely paid attention to Quavo working his clay as they tended to their phones, weed and food. “Come on,” Quavo told Durel, who brough the beat back to the top again and again. Eventually, the sounds started to rhyme. “Chopper . . . Dity . . . Kawasaki chopper, it’s dirty. Thirty . . . Thirty . . . That’s Curry . . . Big dope. Bass drop. Drop-top. Ain’t opp. I can’t stop. Drip wet. Drop-top . . . Brrr brrr . . . Drop my, uh, foot . . . Get in there, get in there, get intere. Diamonds, water, swimwear.”

This was a word game, a crossword puzzle, a rhythmic exercise, and while the genesis may have given ammunition to those who questioned Migos’ lyrical intent, it was an expressionist performance with precision, a conjuring of vibrant imagery where the delivery could invoke as much feeling as the words. Quavo’s early brushstrokes went on for almost exactly five minutes—start, stop, rewind, start, stop, rewind—with no obviously discernible direction, lyrically or melodically, until all of a sudden, he hit on something that made him switch palettes. This sudden lightbulb moment, while simple, seemed to imbue his free-associative mumbling with purpose.

“Just look wiiide awake,” he rapped, clipping the final word. “I’m gonna go count this cake / Make ‘em look wide awake / Take your bae on a date.” It was basic, but it had bounce.

“One more time.”

“Just look wide awake / Take your bae on a date / N—— might pull up on skates.”

“Keep the first part.”

“Watch these n——s throw shade / Watch these n——s throw shaaade!”

“WAKE UP!” Quavo hollered behind his own voice, echoing the order he’d given to the van barely hald an hour earlier. “WAKE UP!” With those trademark ad-libs added, a Migos song had started to materialize. Quavo hammered on the theme. “Look wide awake! You can’t sleep on a n-----! You know you can’t sleep on me! Know they can’t sleep on me! Know they can’t sleep on me!” And that was how a Migos hook was born.

Coscarelli recounts the studio session brilliantly, interpreting this creative act as a sort of real-time crossword puzzle, an act of generative free-association. It certainly is. It also reads, though, as a sort of coding, a programming of bits of creative capital into a larger mainframe, each unit tinkered with and made presentable before coalescing into a larger whole, meant not only to embody a greater, unified being but also to stand alone as the bit that – against all others – will skyrocket to virality.

It’s an approach to songwriting mirrored by Migos’ approach to releasing music: flood the market with bits of content and wait until one sticks and skyrockets. It, too, is how Quality Control approaches talent cultivation in the book: keep a deep bench of rappers until it’s their time to blow. The name, as Coscarelli notes, is a bitter irony; Quality Control succeeds specifically through quantity.

If a certain disdain comes through in this analysis, it is not that of a rap or lyrical purist. Some of the most creative and profound rap music of this greater era—whether that of forerunners like Lil Wayne and Gucci Mane, contemporaries like Young Thug and Future, or distant peers like Lil B—came through a similar instinct. Boundless creativity begets endless creation, and the Internet is a well-suited vessel to receive, sort, and distribute it. Interpreted generously, the over-saturation I lament is nothing more than the manifestation of a metaphysical reality: one can only be prolifically creative for so long before being forced to retread old or less valuable ideas.

More likely is that what stripped this moment of its joy was not the quantity of output it produced but the flows—rather, streams—of capital that it came to respond to and model itself after. Rap Capital, by telling the story of musical influence and business in the mid-to-late 2010s, is inherently a book about corporate streaming. The shift in Migos’ music from vibrant to limpid, just like the shifts in Young Thug and Future from revolutionary to a touch stale, overlapped almost perfectly with the moment that the ubiquitous corporate streaming services that own all music came to fully embrace and capitalize upon the burgeoning Atlanta rap scene. It does not feel random that the high-water-marks this prolifically-created avant-garde rap came just before streaming shifted away from the Wild Wests of YouTube, DatPiff, and Audiomack4 and into the data-driven, endlessly capitalized worlds of Spotify and Apple Music. The music world, like the world around it, is a prisoner of the infinite scroll. The album has given way to the algorithmically-generated playlist. The snippet is no longer a promise of something to come, but the main attraction. Art, like everything else, is content; the virality machine demands fodder. Toss bait into the ether and let the equations snatch them up.

When Lyor Cohen demanded that Young Thug abandon his patented, infamous creative process, it is because he perceived and endorsed this shift. Cohen, ever a corporate businessman, understood that Young Thug’s commercial ambitions required him to make his gonzo, oddball art legible to fans; what didn’t need saying was that this required turning living, breathing art into readable data for an algorithm. “Let the critics come back to ‘em,” Thug protested, as if there were any critics left. Where the old Internet – and the old Atlanta – rewarded the unconventional, the experimental, and the far-out, this new apparatus, finally colonized by techno-corporate influence, demands iteration upon and repetition of that which has already worked. The only business move left is to go viral, and we are all poorer for it—not because creativity has dried up, but because savvy artists seem to believe that you must connect with an algorithm to have any hope of connecting with an audience.

Rest In Peace, Takeoff; Free Young Thug.

Producer Dun Deal once shared that Young Thug recorded not by writing lyrics, but by drawing pictures on a sheet of paper. “Weird signs and shapes,” he said. Thug himself claims to have never written a lyric because it takes too much out of his day.

Coscarelli includes that Marlo, too, was tragically gunned down.

Thug remains incarcerated at the time of this writing.

Who, shout out, are working to model a way of recapturing that generative vibrancy.