Ten Years of Yeezus

Remembering, for better or worse, the album of a decade

It was a hot May night and I had been drinking and my heart was full and that usually meant staying out as late as I could so that I could feel it all, but that night I had to make it home to watch Saturday Night Live. “NOT FOR SALE,” read the screen behind Kanye’s silhouette, before cutting into the horrifyingly white eyes and jaws of three barking dogs. It had been about two weeks since Kanye tweeted “June Eighteen” – 2013 feels very far away, but remember that this was a time when seeing a Kanye tweet didn’t make your heart sink – and for about two weeks we’d heard that the album, the “dark” Kanye album, “Yeezus,” according to Kim Kardashian, was almost done. And then came the beastly, groaning guitars, then the pounding drums, and then Kanye screamed. I remember the studded leather jacket, and the black Klan hoods, and my aunt scoffing, “what the fuck was that,” because of course she would, and I remember realizing that this was the album to which, for better or worse, I would be bound for life.

Yeezus, unfathomably, turns ten today. Ten years ago the guerilla rollout, “New Slaves” projecting onto 66 walls from Wrigley Field to Belmar, New Jersey, ten years ago the rumors, the murmurs, the anticipation, the reported tracklists, the last-minute verses, the reductions, the rants, the write-ups, the canonizing, the pearl-clutching, the over-intellectualizing, the manic, militant, exuberant release. Ten years ago restraint was brought to the altar and stabbed.

Remembering Yeezus can start to feel like a funeral for the long 2010s and the internet culture that defined the era: the internet that looked like old media but wasn’t, the internet that aspired to a world-building and canonizing of its own, a new guard convinced that the air they breathed would be there forever. Yeezus happened online, and where it ventured into the lived world it did so to be captured in fragmentary, eternal posterity on the internet. You don’t remember the projections of “New Slaves” as much as you do the Vines of those projections, West’s dead, horrified eyes on the W Hotel, the tweets from Frank Ocean’s mother saying “yes, that is my son’s voice.” Yeezus, and the hype cottage industry that fed upon it, did not anticipate the links all going dead. You can find proofs if you look hard enough – confirm from blog writeups that Kanye did post an insane American Pyscho remake with Kardashian hanger-ons, a cryptic video of him recording “I Am A God” at Rick Rubin’s house, a brief teaser of “Bound 2.” Still, sift through dead links long enough and it’s easy to convince yourself that it was all in your head. 2013: a time where we all were naïve enough to believe the internet wouldn’t collapse underneath its own weight.

Yeezus still sounds immediate, both recognizable and shocking, hardly a day old. Like any great album, it reveals a new dimension upon each listen; where it stands alone is that each revelation is slightly stupider than the last. In other words, Yeezus remains a triumph because it no longer has to be a masterpiece. After a decade of Kanye’s shameful public flailing, Yeezus is no longer the signature provocation; after a decade of uneven and predominantly awful music, Yeezus is no longer the departure from form; after a decade of transformation from brilliant lightning rod to shameless grifter, Kanye no longer demands breathless attention. An author dies and a text is liberated.

Yeezus, like any religious tale, begins with a birth and a baptism. Press play and hear a synth writhe in birthing throes, pure force, unbridled and apparently untamable. Then hear it take shape – the buzzsaw channeled into something like focus, the drums corralling the structure into place. Hear Kanye, finally, not a conquering hero atop his horse but a man swallowed by the churning river. In a felt and considered remembering of one of 2013’s other masterpieces, Deafheaven’s Sunbather, Jay Papandreas recalls pressing play and having his understanding of a genre’s possibilities blown apart:

Do you remember the first time that you heard, “Dream House”? When I pressed play on a SoundCloud link to the single’s streaming premiere, it was unlike anything I’d ever heard. I remember it absolutely shattering my idea of what black metal should sound like. Outside of Loveless by My Bloody Valentine and Lord Willin’ by Clipse, I’m not sure there’s an album that better prepares you for its sound in its first five seconds than Sunbather. It’s like walking into the parking lot after a three-hour movie. It’s the same buzzsaw guitar that every black metal album uses, but this time, it comes out as a blast of light interrogating every shadow.

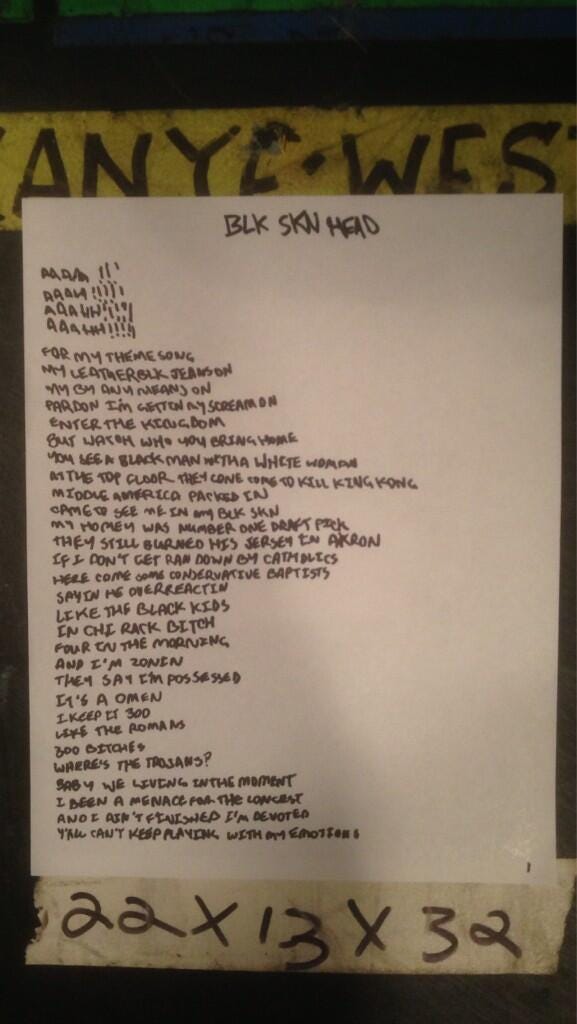

I would contend only that he forgot Yeezus and “On Sight.” As an initiation into the record’s operating logic and aesthetic, the track approaches perfection. Over a lurching and abrasive synth-forward instrumental courtesy of Daft Punk (who in their own work had by then smoothed their sound down to a meticulously unthreatening disco sheen), Kanye starts his “punk” album with an indignant tirade. The music of “On Sight” fools you into the illusion that Kanye, in his purported stab at minimalism, has channeled out the noise; his lyrics make clear that he is hollowing out sound only to clear more room for his own. Immediately a condemnable Parkinson’s pun, regrettable sexual stumbles, form without content. Then the choir sample, a provocative “fuck you” to the pink polo fans who would roll their eyes until the album’s final track. Kanye told Jon Caramanica that he was done apologizing; “On Sight” suggests that the only other option is to get in your face.

In a characteristically perceptive review for the now-defunct Tiny Mix Tapes, Alex Griffin wrote that Yeezus:

breaks into two unequal halves. There’s the devastating opening run of four songs, which is a devastating call to action that’s basically been unseen in mainstream hip-hop for decades, and there’s the next, which is a dark twisted fantasy of fucking, nightclubs, money, bitches, shame, and discomfort, delivered by a man who knows exactly how fucking wrong he is and exactly how much he’s not going to extricate himself.

When I think of Yeezus, it’s those first four songs I conjure most. I think about waiting in the sweaty throng at Randall’s Island for the lights to turn on – again the snapping dogs, the fighter planes, the blood-curdling shrieks from West in his first-ever performance of “I Am A God.” At the Governor’s Ball performance, where Kanye offered proper debut performances of about half of Yeezus, these first four tracks took center stage. The haywire electronic furor of “On Sight,” the not-so-soccer-chant “Black Skinhead,” the operatic show-stopper “I Am a God,” the breathy and panicked immediacy of “New Slaves.” The songs were not yet finished – in light of West’s constant, rushed tinkering, could they ever be said to be truly finished? – but they cut a stark profile. Governor’s Ball was not the Yeezus tour, equal parts opulent and minimal, an artist at the height of his powers; Governor’s Ball was a proof of concept. On the ferry ride home, I felt the fervor of a convert.

Yeezus is the great pop album of our times because it represents the central paradox of the long 2010s, a decade of cultural production dedicated to using the apparati of the world existing around it while standing in open hostility to them. This was the decade that foresook the mainstream for the avant garde while still demanding that the popular acknowledge the outre. Most importantly, it was the decade of stripping back everything until the product was only yourself—the decade of sublimating every influence, every outside force, every loose thread of culture and society into the magnificent, all-powerful ego.

Meaghan Garvey writes that “West has always been a conductor in not just the musical sense, but the electrical – one through whom currents run, for better and now, for worse.” It’s an observation worth exploring. Kanye, ever the contrarian, has never purely mirrored the zeitgeist even when, at the height of his influence, he exerted great control over it. But it would also be too simple to paint West as the sort of artist and public figure who has made a career exclusively out of reaction, provocation, resistance. At his best, West was among the most perceptive trend-spotters of a generation, a seer in his own right. And so Yeezus felt in 2013 like a revalation in part because it found West in total control of his power of sight: the power to identify those values polite society has internalized as unspoken truths, the foresight to recruit the pioneers—from SALEM to Arca to Hudson Mohawke to Gesaffelstein to Chief Keef—who would shape a decade’s sound, his understanding about what made culture in that moment tick. Yeezus like a drone strike at the peak of the Obama consensus years, voicing an unmappable rage that few had the ears to hear. You can see the seeds germinating of the Kanye to come, a man who could not distinguish thoughtful confrontation from shameless provocation: the tour merch, the iconography, the constant listing of “great men”.1 If this is Yeezus, a primal scream from a seer right before the world as legible to him collapsed for good, then the record is best understood as the start of a Greek tragedy.

The Billboard 2013 Year-End Hot Hot 100 Chart, an excerpt:

1. Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, featuring Wanz: Thrift Shop

2. Robin Thicke, featuring T.I. and Pharrell Williams: Blurred Lines

3. Imagine Dragons: Radioactive

4. Baauer: Harlem Shake

5. Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, featuring Ray Dalton: Can’t Hold Us

6. Justin Timberlake: Mirrors

7. P!nk, featuring Nate Ruess: Just Give Me a Reason

8. Bruno Mars: When I Was Your Man

9. Florida Georgia Line, featuring Nelly: Cruise

10. Katy Perry: Roar

11. Bruno Mars: Locked Out of Heaven

12. The Lumineers: Ho Hey

13. Rihanna, featuring Mikky Ekko: Stay

14. Daft Punk, featuring Pharrell Williams: Get Lucky

15. Lorde: Royals

16. Taylor Swift: I Knew You Were Trouble

17. Miley Cyrus: We Can’t Stop

18. Miley Cyrus: Wrecking Ball

19. Avicii: Wake Me Up

20. Justin Timberlake, featuring Jay-Z: Suit & Tie

Yeezus is, of course, the pretentious auteur record from the pretentious auteur of a generation, but before you roll your eyes remember what it felt like to turn on the radio.

Or maybe Yeezus has no political, moral, or artistic content past its surface level. Maybe Kanye has only ever been guided by his blind and unquenchable ego, groping and grasping for a handhold into relevance. Maybe Yeezus is just a stopped clock viewed at exactly the right moment.

Kanye’s ego was never a secret; all that’s changed are its manifestations and defenders. In 2013, Kanye’s ego/monomania was perceived as something of a grand political statement: a radical assertion of Black celebrity, the rough edges on the mind of a genius. In certain corners of culture it felt like a moral obligation to defend Kanye West against the prudes, the prigs, the polite moralists, the ones who cried for Taylor Swift and George W. Bush. Paul Thompson, in remembering the Yeezus press tour, conjures the moment well: “These interviews were mocked and derided by some and parsed for scriptural meaning by others, the way everything Kanye does and says is alternately mocked and bronzed.”

People didn’t view themselves as minor celebrities or celebrities-in-the-making just yet—the dark promise of the internet had yet to fully reveal itself—and so they chose celebrities to stand behind as avatars. Kanye pissed off the worst people while making music in rooms with the best, Big Sean and CyHi the Prince notwithstanding. People may have conflated the art with the artist, for what is Yeezus without the brash man ranting all around it, but this was before everything and everyone had become an equally exchangeable unit of data.

Listening to Yeezus is complicated now by the West to follow. It used to feel like Kanye was a singular mind – a man whose commitment to discerning truth and manifesting his vision might lead him astray to the untrained eye, but whose process always tended in the direction of brilliance, of world-building, of ushering in something new. It doesn’t feel that way anymore, having watched him deflate into nothing more than a charlatan and provocateur, a master collaborator who lost the ability to discern the wheat from the chaff, a narcissist surrounded by parasitic sycophants and yes-men who allow him, time and time again, to make a fool of himself, to spew hate, to provoke for provocation’s sake, to grift and flail as a final cry against the threat of irrelevance, to him the cruelest sort of death. The consummate celebrity now looks, at best, like a fool. But his cruel stumbling, shameful, regrettable, and condemnable as it is, serves oddly to liberate Yeezus. Yeezus is allowed to thrive without being burdened as genius. It is, on its own terms, an eminently stupid and foolish album. It’s a record where 10 artists collaborated on each song and yet lyrics appear to have been jotted down in 15 minutes, where mad dashes to production deadlines produced an uneven and hollow sound that somehow works to its benefit, where Kanye rhymes “bad reputation / sad reputation / mad reputation / Brad reputation.” It is not a masterwork for being considered, but because it zapped into being at precisely the right time. Take the Virgil Abloh-designed cover: it’s just a CD with a piece of red tape, you see, captured at the exact moment at which the light refracted. It looks like you might see God.

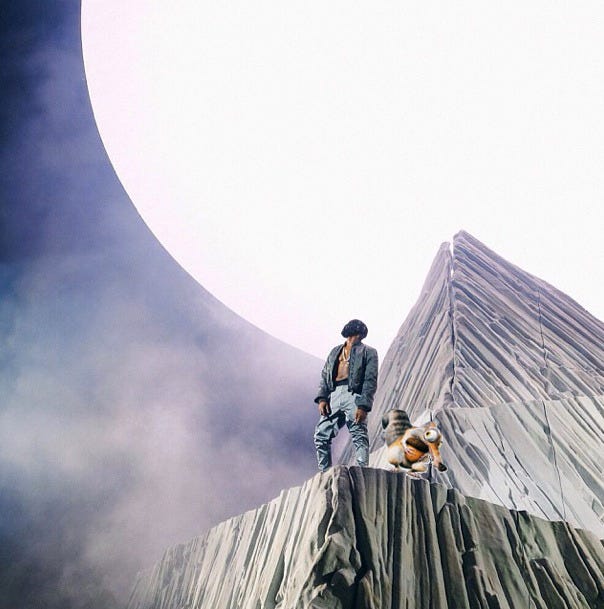

And so Yeezus is freed to be perhaps what it always was: the ego album for an ego decade. Yeezus, a masterwork of cross-genre collaboration, lists only one feature: God. It is the album of the future not just for its affected minimalism, its electronica, and its contrived darkness, but for its total and sole service to the self. It’s a record where civil rights iconography and generations of political struggle are rendered as vehicles for Kanye to fuck: putting TNGHT over “Strange Fruit” to pant about the first time his ex took Molly, the fisting line I needn’t type, “your titties, let ‘em out, free at last.” It’s the biggest rockstar on Earth celebrating the freedom to do whatever he wants, moments before he fell prisoner to the drive to do what he could not. Surroundings are stripped down only so that Kanye can come through brighter. We remember the Yeezus tour for the mask Kanye wore, but remember that the mask was totally bejeweled, that he stood atop a man-made mountain. Yeezus presages a decade in which politics will be worn on sleeves to accrue social capital, in which everything comes second to the self, in which meticulous and intentional curation of image is passed off as considered minimalism. There is a disciple in each of us yet.

The first time I really heard “New Slaves” was June 14th, the day the album leaked, having run home from the movies to get my hands on a .zip file. I’d heard versions and arrangements before – first the series of Vines from the projection, then on SNL, then live in concert. But “New Slaves” doesn’t work unless you are alone with it in its entirety. The song appeared to contain the album’s promise. It was bare, clearly having been reduced from its original form, but it teemed with negative space. Each plink of the synth stood on its own not as less for less’s sake but to create the feeling that you were listening inside of a crumbling cathedral, the sound dancing along walls and caverns, surrounding and suffocating you. It was the purest, most focused distillation of rage I’d ever heard from Kanye, an on-stage rant from which all fat had been trimmed; a political rage, a personal rage, an existential rage. I heard what Kanye wanted me to hear: I seethed with anti-corporate fury, I somehow convinced myself that the fashion industry mattered to me, I loathed the reporters, the private prisons, the smug fucks counting their dollars in their shining white Hamptons houses, and then I felt the euphoric release of the outro, the liftoff, the pure catharsis of the breath you take after regaining your vision. I heard the genius, precise vision that I would come to hear all over Yeezus, because “New Slaves” would come to make every idiosyncrasy and misstep feel as if it were by design.

Listening to the song now can feel like a sort of betrayal. It’s hard to have identified so closely with a rage that only ever belonged to and contemplated one person, hard to make sense of the song that defined your formative years being motivated by little more than a beef with the fashion industry. “New Slaves” sounds differently when you realize that Kanye’s only beef with the Hamptons was his not being invited.

There’s a picture of one of the “New Slaves” projections from the W Hotel in Los Angeles. People flock to the scene; one man films from atop the roof of a car. From afar, Kanye’s eyes are horrifying: the white above his eyelids gives the impression that he has seen something he cannot unsee, his face petrified in a shocked death mask. But the closer you get to the image, the more you realize that it was just a reflection. In reality West’s eyes are drooping, nearly closed, listless.

But then it doesn’t really matter, does it? Isn’t that the thing with art – that you can divorce the art from the artist, even with art as egomaniacal as this? That you can stand as far or as close as you’d like? That for four minutes and seventeen seconds you can pretend that it all stopped right there, that you’re still where you were the first time or the tenth time or the hundredth time and you can remember, with immediate and exact clarity, the way it felt to not know how this was all going to turn out?

As a rule of thumb, it is safe to assume that anybody who pathologically lists and compares themselves to the “great men” of history has one more name in mind that they feel, unless they’ve gone through a public divorce, would be a bit untoward to mention.

👏👏👏👏👏👏👏