The Promise and Heartbreak of Tha Tour, Pt. 1

Ten years of faith, memory, and Rich Gang

Rich Gang: Tha Tour Pt. 1 begins with a lie so profound that I named a blog after it. “We never hungover—never, boy,” boasts Birdman in what amount to the tape’s introductory remarks. It’s a throwaway flex amidst a soliloquy of marble floors, gold terlets, and chandeliers, the type of obviously untrue non-sequitur that inclines listeners to roll their eyes and fast forward to Young Thug’s breakneck rapping. A confession: I used to think the Birdman monologue was stupid. But at some point during the ten years of Tha Tour’s existence, I’ve come to understand Birdman’s meandering opening as, if not a skeleton key to the mixtape, then at least an apt introduction to Tha Tour’s singular logic. Rappers lie…all the time. There’s no story there. But from a ten-year remove, “we never hungover” reads less as a thrown-off lie than it does a stage-setting device for Tha Tour as a piece of speculative fiction. It’s not possible, right, to pair GTV and tequila with stunna blunts and never get hungover; but for some 85 minutes during which the dates are, until time immemorial, locked in, you believe it is.

My hope, basically, was to try and find a way to write a ten years of Tha Tour piece that didn’t just feel like another tired celebration of an anniversary; something that went a bit further than “remember when we were younger and things felt new and possible?” The idea being, more or less, what if we treated Tha Tour not as a missed opportunity, but a portal into a world where there was a tour? A pt. 2? Where the record’s vibrancy was continuously channeled further and further into the outré, where saying Rich Gang in public meant someone would, out of muscle memory, respond Rich Girl? It was supposed to be fun, if a little silly, not unlike the record it meant to celebrate. But then Rich Homie Quan tragically died at 34 years old, and Young Thug remained incarcerated throughout a Kafkaesque, interminable prosecution, and thinking about and listening to Tha Tour felt impossibly sad.

Tha Tour is a record composed almost entirely of promises, which makes listening to it akin to an act of faith. It was conceptualized both as a showcase for two of Atlanta’s budding stars—the immediately venerable hitmaker Quan and the garbled, initially unquantifiable Thug—and as proof of concept for what might have been understood as the second iteration of Birdman’s reign as kingmaker at Young Money Cash Money Billionares. The tape doesn’t read like that now, but the anachronisms are everywhere; it is the distinct product of a bygone moment in rap culture, distribution, and gatekeeping. Rich Gang is better understood as a corporate fiction than a rap group—its members were entirely replaceable, its purpose solely to audition and stamp the broader constellation of the YMCMB prospect pool. It is, conceptually, more than a bit of a mess.

In other words, the best rap record of the last decade was meant to serve as a promotional flyer. If you don’t believe me, look at the garish, low-rent album artwork (replete with subsidiary brand logos) of Quan and Thug’s faces joined in a proto-XXXtentacion tribute superimposed upon Birdman-as-star, imagery that intended to speak in the language of Freud but came out talking like SpongeBob. Tha Tour was an entree, a self-fashioned part one. It’s this fact—that Tha Tour was never meant to stand on its own—that lends the tape its breathtaking serendipity.

For a long time, there was a perplexing, vaguely racist prevailing sense that Young Thug’s music defied linguistics. Critics liked to fashion it “post-verbal.” Over the course of five minutes, give or take some Birdman shenanigans, “Givenchy” should have put that line of thought to bed before it ever took hold. “Givenchy” is a sprawling, deconstructed missive. Thug begins by piecing together something like a traditional hook before toying with a sing-song flow punctuated by increasingly urgent ad-libs. Before long, his cadence is desperate, frenetic, manic. There’s really no writing about this stuff, just go listen, hear how he describes splitting up the money eight ways like he’s an octopus. The magic of Young Thug’s linguistics is not that he transcends them, but that you have never heardwords imbued with such meaning. Here, on “Givenchy,” is a man whose lyric sheets consist of doodles rather than written words, rapping like the rent is due—or, more likely, like the dates weren’t yet locked in.

Two weeks ago, a video circulated the internet purporting to show Rich Homie Quan’s son “getting emotional while rapping his song word for word” at Quan’s funeral. I avoided the video for as long as I could; the visceral pain of Quan’s death was still so raw, and I was inclined to find aggregating videos of his family’s pain repulsive. It never crossed my mind that his son would be rapping anything other than one of Quan’s radio-ready, titanic hooks. It was in disbelief, then, that I finally watched a video of Rich Homie Quan’s son rapping “Milk Marie,” a ballad to one specific vagina, in which Quan name-checks Osama Bin Laden for the second time in Tha Tour’s 85 minutes.1

“Milk Marie” is one of Tha Tour’s many single-artist ventures; as with them all, you can hear Rich Gang’s second half lurking just behind the mix. Just as Quan’s immediately legible, ear-worming sensibilities bring Thug into focus throughout the tape, Thug’s disjointed, staccatoed DNA is all over “Milk Marie.” Thug and Quan unlocked something in one another, an alchemical mixture of boundless exploration and an immediate knack for melody, that imbues almost all of Tha Tour’s twenty tracks with a sense of magic. Tha Tour is a great mixtape not because it is a display of virtuosity for its own sake, but because this magic is immediately infectious. You don’t need to revisit Quan’s son’s grief to understand what I’m talking about—just watch the video of the phenomenally ambitious DJ Fresh turning the pre-Tour “Lifestyle” into an American Idol audition. It’s not just an exercise in nostalgia for an internet capable of circulating “bro was trying to get signed” whimsy, but a reminder of how it felt to go outside and be struck by lightning again and again.

You can’t watch this video without thinking of “Freestyle,” the pound-for-pound standout of Tha Tour’s 20-track run. “Freestyle” is, as billed, pure rapping. It is style completely transcending the constraint of hook, structure, or convention. Quan cycles through flows in his introductory knockout, but his first is his most evocative. The sentences barrel forward:

My baby mama just put me on child support

Fuck a warrant, I ain’t going to court

Don’t care what them white folks say, I just want to see my lil boy

Go to school, be a man, and sign up for college boy

Don’t be a fool, be a man, what you think that knowledge for?

There’s no writing a ten years of Tha Tour piece because for 9 years, 11 months, and one week of the tape’s existence, those lines made you beat your chest. Now, they are salt in the wound of unspeakable tragedy.

In his equally somber and celebratory memorial for Rich Homie Quan, Paul Thompson theorizes a justification for “Type of Way” as perhaps the sole anachronism in Uncut Gems. The Safdie brothers, Thompson imagines, sacrificed their otherwise faithful 2012 mis en scene for the emotional punch of the gigantic single: “this, in so many ways, sums up Quan’s career: unstuck in time ever so slightly, caught between eras, yet still, on the most fundamental level, undeniable.”

With Tha Tour, Pt. 1, I’d take the proposition even further. The record is so singular that with enough listens, you come to understand it not as a happy accident but as a wedge into a universe so near our own. What do you do when the most single-ready, fully-fleshed song on a record made to promote a tour that functionally never happened, a track throughout which Rich Homie Quan croons and Young Thug imagines looking “over these bitches like terms and conditions,” is called “Tell Em (Lies).” It’s tempting to read too much into Tha Tour’s Borgesian fantasy; as a matter of fact, I should probably stop. But there is something about Tha Tour, in light of the tragedy that would come to follow, that demands poring over—the sense not just that with the next listen you can recapture the feeling of the first autumn moment you pressed download on DatPiff, but the nagging feeling that you might finally hear the serendipitous ad lib that snaps you out of it, reminding you that, yes, of course the tour did happen, of course the dates were locked in, of course they were brothers for life, of course it didn’t end like this. That it went a different way because it had to, because what you’re hearing is incompatible with what you think you know.

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 begins with the story of four academics and critics obsessed with the impossibly mysterious German author Benno von Archimboldi. The four critics fashion themselves experts on Archimboldi’s ouvre, which entails proclaiming the anonymous Archimboldi as the literary voice of a generation. The search for Archimboldi takes three of them to the blood-soaked, industrialized Mexican border city Santa Teresa, a fictionalized version of Ciudad Juárez. They don’t find him.

By the time Bolaño introduces the reader to Archimboldi, he has already subjected them to a clinically detached 304-page barrage of femicide. As in the real life Juárez, a set of men in Santa Teresa are murdering women and a set of men are laughing about it as they sit on their hands; one can imagine a not insignificant overlap in the Venn diagram. Bolaño allows you to meet his hidden author only after you have contended with true horror and tragedy. He dares you to still care about meeting the genius.

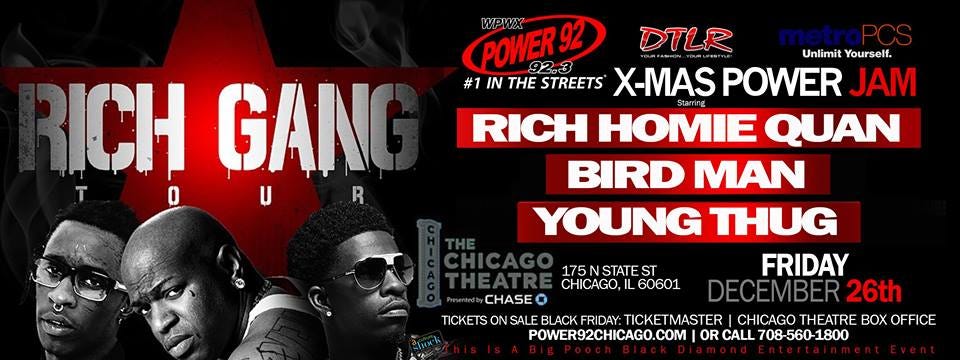

What I mean to say is there was a tour, or at least a single confirmed show. Throughout Tha Tour, listeners are promised not only that the dates are locked in, but that “October 31st is the start.” It’s not clear a Halloween show ever happened, but on December 26, 2014, the day after Christmas, Rich Gang played a show at the Chicago Theater.

It happened. People saw it, there are videos, and you can watch them. They don’t bring Rich Homie Quan back, and they don’t let Young Thug free, but they are there. You can watch clip after clip of Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan prowl across a stage shared with, conservatively speaking, a hundred other people. In nearly all of these videos, Birdman stands between the incendiary duo in a sort of show of his kingpin power. But during “Lifestyle,” nobody comes between Rich Homie Quan and Young Thug. Everybody is a part of the celebration, but it is their show.

When I searched “Rich Homie Quan Son” on Twitter to find the video, the third result was a 2015 Complex article titled “Rich Homie Quan fought a security guard at LIV then escaped on a speedboat.” The photo, a picture of Quan solemnly saluting, filled me with a brief gasp of joy.

the chefs kiss here is that half the videos aren't embeddable or are taken down

this was 🤌🏽